Table of contents

I. Summary

Technology industries hold out the potential for decentralized economic vitality. However, for decades, tech has remained highly concentrated in a short list of coastal “superstar” cities—places such as San Francisco, Seattle, and New York.

More recently, though, the rise of remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic has spawned new hopes for the spread of tech jobs into the U.S. heartland. Given that possibility, this report probes the latest trends in the geography of tech over the past decade and through the pandemic. Specifically, the analysis examines detailed employment data as well as location-specific job postings to assess local and national hiring trends. Data on firm starts is also examined. Among the findings are:

- Growth in key tech industries has been rapid and resilient in the last decade, including through the pandemic. Software publishing and other information services have led the way.

- The tech sector has until recently been concentrating, not decentralizing. Prior to the pandemic, tech was adding jobs across much of America, but it wasn’t really “spreading out” in terms of more cities increasing their shares of the sector’s jobs. Instead, coastal “superstars” like the Bay Area and Seattle predominated.

- With that said, the pandemic years seem to be distributing somewhat more tech activity into a wider set of places. This shift does not represent a massive reorientation of tech work into the heartland during the pandemic. However, the data in this report shows that employment growth slowed in some of the biggest tech “superstars” and increased in other midsized and smaller markets, including smaller quality-of-life meccas and college towns.

II. Introduction

For decades, technology visionaries have dreamed that an explosion of decentralized work would bring about “the death of distance”—journalist Frances Cairncross’ term for the space-collapsing effect of the internet, including the dispersion of tech activity into new places, such as the U.S. heartland.

More recently, rising concerns about the nation’s economic divides have sharpened the hope that the spread of tech jobs into “flyover country” would allow struggling Main Street communities to participate more fully in the economy.

However, relatively little of that diffusion has happened in recent decades, even during the social media boom of the 2010s. Tech employment grew in many regions, but the nation’s “superstar” hubs in the San Francisco Bay Area and elsewhere grew even faster, concentrating their dominance. Instead of the “rise of the rest,” a term coined by AOL co-founder and investor Steve Case to refer to the growth of startup ecosystems away from the coastal tech hubs, the geography of the tech sector solidified into an uneven “winner-take-most” dynamic.

Now, though, the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of remote work have brought an array of intriguing new signals.

A 2021 survey by the San Francisco venture fund Initialized found that 42% of its firms’ founders said that if they were starting a business today, their preferred “place” to launch it would be through remote or distributed work. More recently, research by PitchBook and the Washington, D.C.-based investment firm Revolution reported that the share of early stage venture capital dollars going to non-Bay Area startups was on pace to exceed 70% in 2021—up from 60% in 2014. Meanwhile, major tech companies such as Palantir, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Oracle, and Tesla have moved their headquarters from California to Denver, Houston, or Austin, Texas. During the pandemic, Google and Apple announced major satellite and engineering offices in North Carolina. And Intel recently announced the siting of two semiconductor plants in the Columbus, Ohio metro area, prompting excitement about the rise of a “Silicon Heartland.”

So, is the long-awaited “rise of the rest” actually happening? To investigate that question, this report provides a new look at recent and emerging geographic trends to assess the extent to which the tech sector has been spreading out or concentrating.

Specifically, the analysis employs detailed employment data (rather than survey information) as well as thousands of location-specific job postings to assess local and national hiring trends both before and during the pandemic. Data on firm starts is also examined. Focusing on this information yields several findings about the growth and geography of tech in recent years. Among the findings are:

- Growth in key tech industries has been rapid and resilient in the last decade, including amid the pandemic.

- The tech sector has until recently been concentrating, not decentralizing. Prior to the pandemic, tech was adding jobs across much of America, but it wasn’t really “spreading out” in terms of more cities increasing their shares of the sector’s jobs.

- With that said, the pandemic years may be distributing more tech activity into a wider set of places. This shift does not depict a massive reorientation of tech work into the heartland during the pandemic—in fact, the biggest established hubs as a group slightly increased their share of the sector’s total nationwide employment. And yet, the data in this report shows that employment growth slowed in some of the biggest tech “superstars” and increased in numerous other midsized and smaller markets, including smaller quality-of-life meccas and college towns.

Whether these trends forecast a durable shift or a temporary disruption, the new figures support at least for now the possibility of a greater diffusion of tech activity in the coming years.

III. Background

A few notes of context are needed to situate the current moment in tech geography. After all, major swings in the nature of the U.S. economy have shaped and reshaped the nation’s economic geography in recent decades. Such swings suggest alternative paths for the post-pandemic future.

Postwar convergence, followed by divergence

For much of the 20th century, market forces tended to reduce job, wage, investment, and business formation disparities between more- and less-developed regions. Consequently, disparities between places tended to dissipate as the economy grew. Even seriously lagging places often “caught up” as business ideas diffused and cost differentials motivated people and firms to relocate to lower-cost regions; witness the rise of the South as regional pay and employment gaps narrowed in the post-World War II economy. Market forces were bringing about “convergence” among communities.

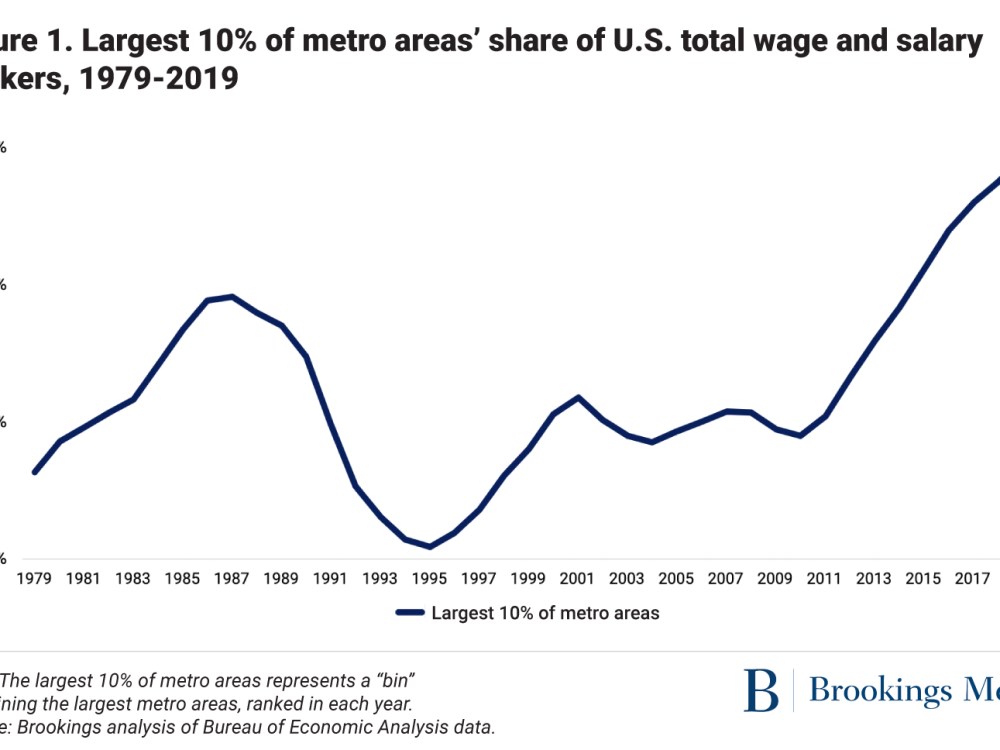

Yet in the 1980s and 1990s, the convergence trend started to break down, especially as digital technologies and innovation began to dominate. Since then, intense new demands for talent—all hitched to gigantic platforms and global electronic networks—have increased the power of “agglomeration” economies, unleashing self-reinforcing dynamics that have increasingly rewarded workers and companies for clustering together in dense, tech-heavy urban areas, especially big, coastal cities.

Amid these “winner-take-most” conditions, the convergence of cities gave way to their divergence in the 2000s. Soon, the leading 10% of U.S. metropolitan areas—which included tech-driven cities such as San Francisco, Boston, and New York—begun to pull away from other regions on measures of pay and employment, with a surge in the last decade.

By the middle of the last decade, a handful of dynamic coastal metro areas—most notably the Bay Area, Seattle, and Los Angeles—had emerged as dominant hubs of both tech and the rest of the economy. By contrast, scores of heartland cities, small towns, and rural areas were going sideways or falling behind on basic indicators of innovation, output, and income.

Regions’ possible futures amid pandemic disruptions

So now what’s happening? Given fast tech growth during the pandemic and the national experiment with remote work, it is important to examine the latest trends in tech geography to assess possible futures as the COVID-19 crisis eases.

New research by Stanford University economist Nicholas Bloom suggests the potential for both a “winner-take-more” trajectory (major gains for only a few places) and a “rise of the rest” scenario (more broadly dispersed opportunity across many metro areas). On the one hand, Bloom’s study of the rollout of 20 new technologies during the 2000s shows that the earliest stages of tech emergence often concentrate the bulk of job growth close to the site of the original innovation. On the other hand, Bloom reports that in later development stages, a greater portion of employment associated with new technologies diffuses more widely, as earlier-stage innovation gives way to more routinized business activity.

Given that, the ongoing development of the U.S. tech sector holds out the potential for multiple scenarios for local tech ecosystems, firm siting, and development leaders. In view of these alternative scenarios, a data-driven look at recent and ongoing trends in tech geography is in order, as workers, firms, builders, investors, and development professionals begin to map their next moves.

IV. Approach

To assess these issues, this report tracks the growth and change of a defined technology sector as it proceeds across multiple geographies and time periods.

Defining the technology sector

This report defines the technology sector as a six-industry subset of the nation’s “advanced industries”—a Brookings grouping of the nation’s highest-value innovation industries:

- Computer and peripheral equipment manufacturing (including companies such as Dell, Apple, and Western Digital)

- Semiconductor and other electronic component manufacturing (e.g., Intel, Nvidia)

- Software publishers (e.g., Microsoft, Salesforce)

- Data processing, hosting, and related services (e.g., Amazon Web Services)

- Other information services (e.g., Google, Meta, Netflix)

- Computer systems design and related services (e.g., IBM, Accenture, and Tata Consultancy Services)

Mapping the technology sector

Mapping the technology sector

Given this report’s focus on tech’s spatial patterns, our analysis reports major industry trends as they play out across the nation’s main geographical units: the nation as a whole and the nation’s 100 largest metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), which account for 81% of U.S. tech sector employment as defined here. MSAs (or “metro areas”) are central to the analysis because they are the nation’s core economic units.

In addition, special attention is placed on eight mostly large, long-established, and growing tech hubs—sometimes deemed tech’s “superstar” metro areas:

- San Jose, Calif.

- New York

- San Francisco

- Washington, D.C.

- Seattle

- Boston

- Los Angeles

- Austin, Texas (although smaller than the other established hubs, Austin is included given its longtime importance and fast growth)

Tracking metro areas’ growth and change

To assess the pace and shape of tech trends, our analysis tracks tech-sector employment growth and change across the largest 100 metro areas during several time periods. Broad context is provided by reporting on tech growth during the 2010s decade in full, while the core analysis reports growth and change during the years 2015 to 2020—reflecting pre-Covid trends as well as the latest available data for the first year of the pandemic. Data are segmented to allow comparison of trends in the pre-pandemic years (2015-2019) with trends in the first year of the pandemic (2020).

For these analyses the report employs high-quality data from the labor market research firm Emsi Burning Glass (EmsiBG), derived from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). This annual data allows for the highest-quality, most reliable analysis of on-the-ground employment trends, but is only available with coverage up to 2020.

To probe more recent trends during the pandemic, the report supplements the EmsiBG employment data with job postings data from EmsiBG and data on new firm starts from Crunchbase. The job postings data, covering September 2016 to December 2021, provides a rough assessment of growth trends, in that they measure the characteristics of open positions (though not necessarily the nature and number of actual hires). They represent a near-real-time data source that allows for assessment of shifting trends during the latest phase of the pandemic. The firm-start data from Crunchbase provides an additional reading on the level and geography of tech activity.

To probe more recent trends during the pandemic, the report supplements the EmsiBG employment data with job postings data from EmsiBG and data on new firm starts from Crunchbase. The job postings data, covering September 2016 to December 2021, provides a rough assessment of growth trends, in that they measure the characteristics of open positions (though not necessarily the nature and number of actual hires). They represent a near-real-time data source that allows for assessment of shifting trends during the latest phase of the pandemic. The firm-start data from Crunchbase provides an additional reading on the level and geography of tech activity.

For all of these indicators, special attention is paid to shifts in metro areas’ local shares of the national tech sector. Such shifts are important measures of both the location of tech and the relative local competitiveness of particular markets in comparison to other markets.

V. Findings

Analysis of employment growth, hiring growth, and location trends in the technology sector generates several conclusions:

- The U.S. tech sector has continued to rapidly grow

Throughout the last decade, the U.S. tech sector has been growing rapidly, including during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Taken together, the sector—consisting of four digital services and two slower-growing tech manufacturing industries—grew by 47% in the 2010s, as it added more than 1.2 million jobs. That brought the sector’s total employment to 3.9 million positions in 2019. Given that expansion, the sector grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 4.4% in the 2010s—a rate nearly triple the growth of the economy as a whole.

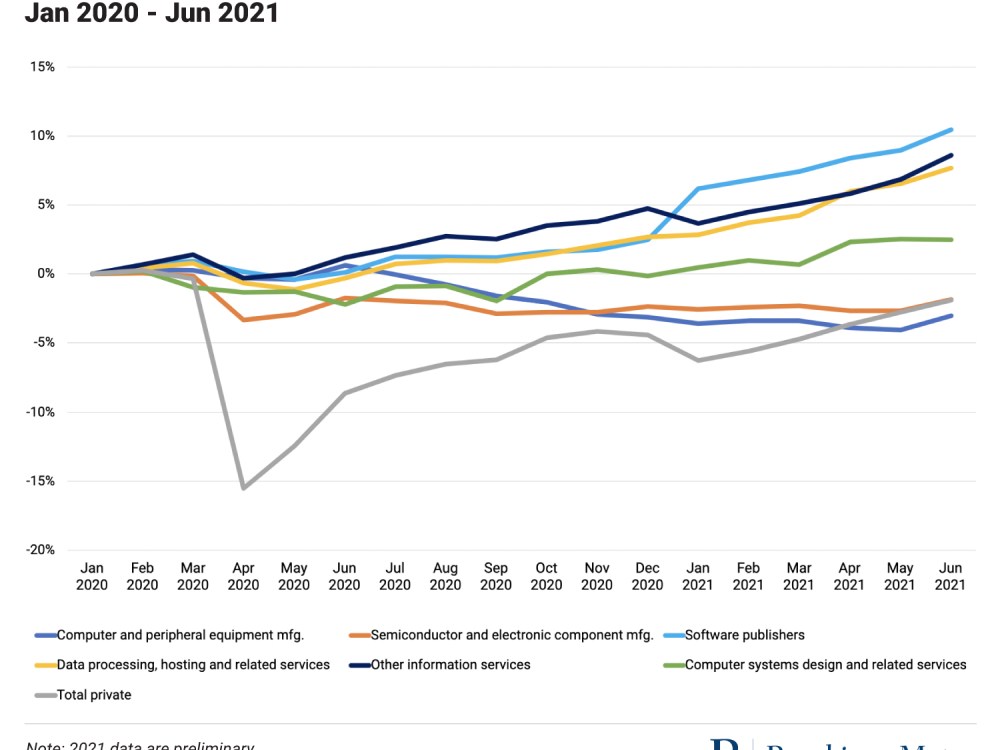

Not even COVID-19 could stymie the sector’s growth. Although the sector’s expansion slowed during the initial pandemic-related lockdowns, it has managed net positive growth through most of the crisis. Propelled by an explosion of remote work, e-commerce, and digitalization, growth turned only shallowly negative during seven months of 2020 before powering forward after fall of that year.

Among the four fast-growing digital services in the sector, three of them (“Software Publishing,” “Data Processing,” and “Other Information Services”) shed jobs in the five months between spring and early summer 2020. But by last summer, these industries saw employment 8% to 11% above their pre-pandemic highs. Only the slow-growing “Computer and Peripheral” and “Semiconductor Manufacturing” industries saw employment growth languish throughout 2020. All of the other industries studied far exceeded their national pre-pandemic employment levels from nearly two years ago.

In sum, most U.S. regions and states and more than half of metro areas have benefitted from tech sector growth throughout the last decade. Between 2010 and 2019, all four major census regions; 48 out of the 50 states as well as Washington, D.C.; and 289 out of the nation’s 384 metro areas have seen positive employment growth in the sector. Among the 100 largest metro areas, 83 have seen tech sector growth. That growth and the rise of consequential tech ecosystems in numerous new areas have licensed optimism about the spread of tech into new places, including the U.S. heartland.

- Tech sector growth prior to the pandemic remained highly concentrated

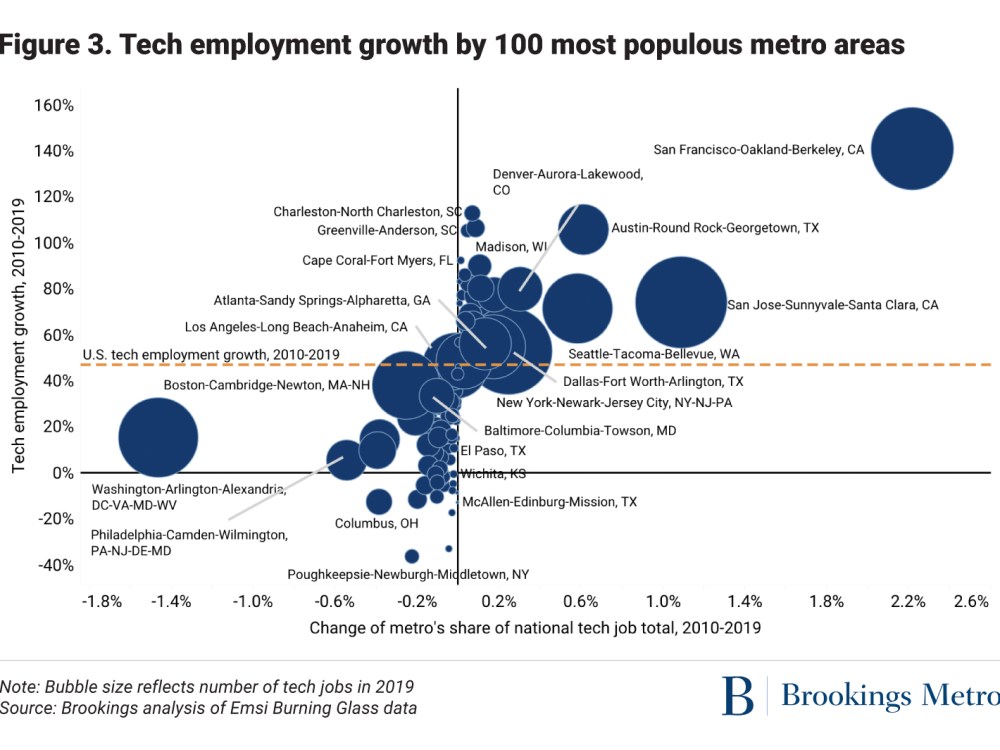

Despite the tech sector’s growth in the last decade, employment in the sector—while positive in many markets—wasn’t really spreading out. In fact, looking across the landscape, tech employment was growing more concentrated into a short list of places.

Focusing on the nation’s largest metro areas, a historically dominant cadre of “superstar” cities and a newer set of “rising star” metro areas were each continuing to extend their ascendency in the years immediately before the pandemic

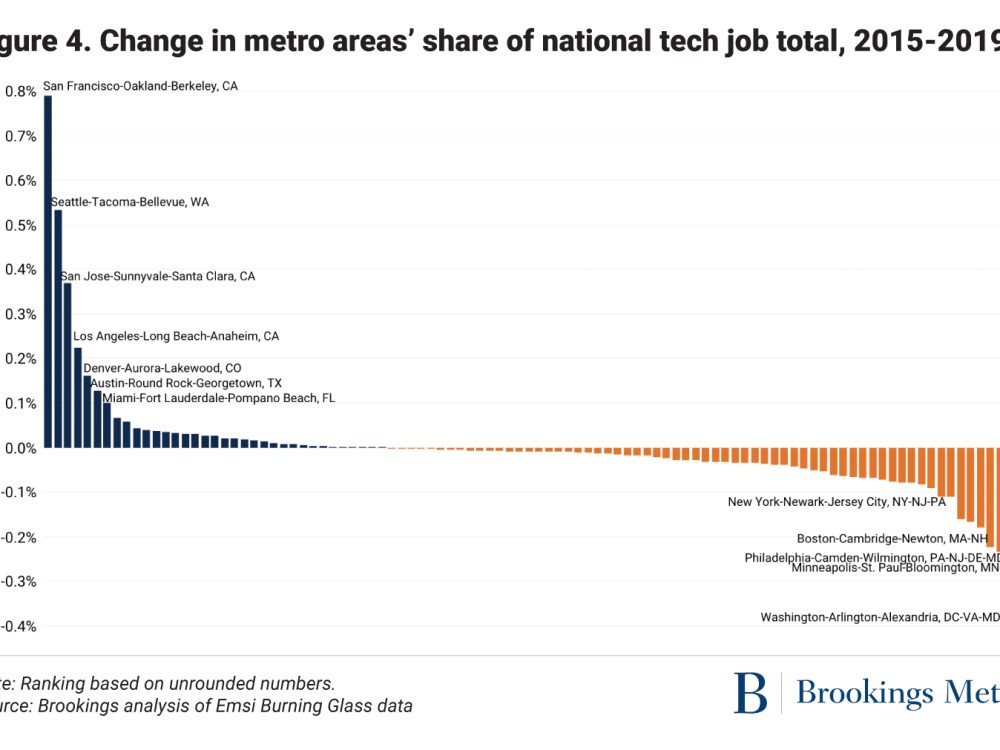

At the forefront, only eight mostly coastal “superstar” metro areas—beginning with San Francisco, San Jose, and Austin, and including Boston, Seattle, Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C.—accounted for nearly half of the nation’s technology sector job creation between 2015 and 2019.

Large and mostly fast-growing, these well-established hubs dominated the nation’s tech growth through the early 2010s and gained dominance in the pre-pandemic years of 2015 to 2019. For example, the two Bay Area metro areas—San Francisco and San Jose—together generated almost 20% of the nation’s entire new tech employment during the pre-pandemic period, increasing their share of the sector’s total nationwide employment by 1.2% (see Figure 4). Likewise, Seattle added more than 40,000 new tech jobs in the period (roughly 7% of the nation’s total), increasing its share of the sector’s total nationwide employment by 0.5%.

Altogether, the eight established hubs encompassed roughly 1.5 million tech jobs as of 2019 (38.2% of the nation’s tech employment), up from 1.2 million and 36.8% in 2015 (even though the East Coast hubs of New York, Washington, D.C., and Boston grew slow enough to slightly lose industry share). Altogether, the eight tech hubs’ share of the sector’s total nationwide employment increased by 1.4% between 2015 and 2019, even as advocates hoped for greater dispersion.

At the same time, a handful of midsized but less-established centers grew briskly in the years before the pandemic, meriting attention as “rising stars.” Mostly situated in the nation’s interior, these nine dynamic metro areas—Atlanta; Dallas; Denver; Miami; Orlando, Fla.; San Diego; Kansas City, Mo.; St. Louis; and Salt Lake City—also increased their share of the sector’s total nationwide employment by adding jobs at a rapid 3% CAGR (or more). These newer centers—which together generated 87,000 new tech jobs between 2015 and 2019—grew their share of the nation’s tech economy by an aggregate 0.5% during those years (see Figure 4). By growing rapidly and increasing their share of the national tech sector, these metro areas were delivering on the promise of tech spreading out to create sizable new ecosystems in the “rest” of America.

However, for the most part tech, was not really spreading out during the 2010s. Beyond the superstars and rising stars, most other large metro areas saw only modest (or negative) tech sector growth and employment share increases in the pre-pandemic years. Figure 4 visualizes this with its long “tail” of metro areas extending to the right of the two dozen or so most competitive metro areas. Altogether, 73 of the nation’s 100 largest metro areas (including the three historical East Coast superstars of Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C.) experienced either negligible, flat, or negative growth in their share of the nation’s technology sector in the pre-pandemic years. Among those metro areas, 24 lost tech jobs in absolute terms during that period. About half of these slow-growing cities lie in the Northeast and Midwest.

Overall, the years 2015 to 2019 saw most of the nation’s 100 largest metro areas add tech jobs, yet only 27 of them added enough to demonstrate significant competitiveness by notably increasing their share of the sector’s total nationwide employment. In short, the pre-pandemic years 2015 to 2019 accentuated the emergence in the last decade of a national tech geography dominated by relatively few mostly coastal winners, complemented by an up-and-coming cohort of “rising star” markets in the nation’s interior. Beyond these two tiers lay scores of urban areas in the nation’s interior that were mostly going sideways or slipping in terms of true competitiveness gains, as reflected by their flat or decreased shares of the nation’s overall tech employment. The tech “rich” were getting richer.

- The pandemic’s first year disrupted tech sector concentration

The tech sector’s “superstar” geography may be entrenched, but it’s not necessarily immutable. The first year of the pandemic showed that. Employment data covering 2020 confirms the extent of early pandemic disruption and the possibility of new growth patterns.

To be sure, the first year of the pandemic imposed no wholesale apocalypse on the nation’s superstar geography. Despite everything, the superstars’ aggregate growth rate remained positive through 2020, to the point that these established hubs further increased their aggregate share of the sector’s total nationwide employment by 0.3%. New York, Seattle, San Francisco, and Austin dominated on this metric, increasing their shares slightly. New York added jobs significantly faster in 2020 than in the previous four years, with its annual growth rate surging from 3.5% to 4.9%.

Rising stars Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Miami, Orlando, San Diego, Kansas City, St. Louis, and Salt Lake City also powered through the first year of the pandemic to turn in positive growth and add a combined 14,000 tech jobs while slightly increasing their aggregate share of the nation’s tech sector. Dallas, Atlanta, Denver, and St. Louis all added tech jobs at annual growth rates in excess of 3%. And St. Louis saw its tech growth rate increase from 3.9% over the 2015-19 period to 4.8% in 2020.

At the same time, 29 large metro areas failed to register tech employment gains, and 62 saw hiring slow in 2020—a sign that not everything has changed with America’s winner-take-most technology geography.

With that said, the first year of the pandemic saw unmistakable shifts in the nation’s superstar-dominated tech geography:

- Tech sector employment growth slowed in the biggest, most dominant tech centers. Notwithstanding New York’s 2020 growth surge, all the other tech superstars saw their tech sector employment growth rates slow—sometimes precipitously—in the first year of the pandemic. Overall, these metro areas saw their 4.9% pre-pandemic (2015 to 2019) annual growth rate slow to 2.9% in 2020. Employment growth in San Jose slowed from 5.3% pre-pandemic to just 1.9% in 2020. In Los Angeles, growth slowed from 5.6% to 0.2%. And in Boston, growth turned negative. Given this, Boston and Los Angeles gave up sector share amid the year’s market gyrations. These shifts signaled potential weakening of the dominant hold of the superstar cohort on U.S. tech growth. Similar patterns played out among the rising star metro areas: Growth among these leading metro areas slowed from 5% a year to 2.9%, as all of the rising stars except St. Louis saw slowing growth (although in none of these vibrant locations did growth turn negative). Overall, then, almost all of the nation’s leading tech centers—including both the superstars and rising stars—saw their growth slow during the first year of the pandemic (though only a few of them also decreased their share of the sector’s total nationwide employment).

- Nearly half of the nation’s 83 other large metro areas saw their tech sector growth rates increase in 2020 compared to 2015-2019. In contrast to the major tech hubs, a significant number of cities in the rest of America saw notable upticks as remote work increased and tech growth spread out slightly in the first year of the pandemic. Altogether, 36 of these 83 metro areas outside the superstar or rising star echelon saw tech employment change accelerate in 2020 compared to the pre-pandemic years. Larger growers included northern business cities such as Philadelphia, Minneapolis, and Cincinnati; sizable warm weather cities such as Charlotte, N.C., San Antonio, Nashville, Tenn., Birmingham, Ala., New Orleans, Greensboro, N.C., Jackson, Miss., and Stockton, Calif.; and a number of substantial university cities such as Chapel Hill, C. and Madison, Wis. Also seeing accelerated 2020 tech growth were numerous lifestyle, Sun Belt, or vacation centers such as Virginia Beach, Va., Ogden, Utah, Albuquerque, N.M., Tucson, Ariz., and El Paso, Texas. In sum, nearly half of the nation’s secondary large metro areas added tech jobs at a faster rate than they did in 2015-2019, when only one superstar and one rising star metro area did.

- A number of smaller quality-of-life meccas and college towns also seemed to add tech jobs sharply during the initial year of the crisis. Among the former group, high-amenity and vacation towns such as Santa Barbara, Calif.; Barnstable, Mass.; Gulfport-Biloxi, Miss.; Pensacola, Fla.; and Salisbury, Md. all saw their tech employment surge by 6% or more. These locations offered proximity to larger technology centers in addition to an attractive quality of life for footloose firms or workers. Likewise, attractive and convenient college towns such as Boulder, Colo.; Lincoln, Neb.; Tallahassee, Fla.; Charlottesville, Va.; and Ithaca, N.Y. all grew their tech jobs by more than 3% during the first year of the pandemic. Smaller-town job surges like these likely reflected the rise of “Zoom towns”: communities bolstered (at least for now) by the remote tech work of new residents whose work relies on digital tools.

While not definitive, these signals from high-quality 2020 employment data suggest at least the temporary emergence during the pandemic of a new kind of two-tier reality that incorporates persistent superstar and rising star dominance paired with a degree of tech diffusion into lower-cost or high-amenity locations.

- More recent data also points to continued pandemic-related decentralization

Higher-frequency, more recent information on local economic activity confirms the impression of modest tech sector decentralization during the pandemic. This data on job postings and firm starts extends the story beyond the 2020 employment data used in this report, and provides additional signs of potentially greater decentralization of tech activity.

Job postings data from EmsiBG suggests discernable shifts of economic activity among cities. While distinct from actual hires and employment, the ebbs and flows of job vacancy advertisements allow visibility into economic activity throughout the pandemic and depict a distinct slippage of the superstar metro areas’ share of U.S. tech activity.

Specifically, the superstar metro areas’ share of unique tech sector job postings—which had begun to decline in the pre-pandemic period—has slipped further in the last two years as postings declined from roughly 40% in September 2016 to about 31% in December 2021. To be sure, three of the nation’s superstars—Los Angeles, Seattle, and Austin—saw their national job postings shares surge as tech job ads there increased by more than 150% during the period. Ads in Austin, in particular, surged massively during the pandemic. However, the share of postings in the five other superstars—San Francisco, San Jose, Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C.—slumped, with hiring activity as measured by job postings sagging by noticeable margins.

For their part, job postings in the rising star cities have increased as a share of U.S. tech postings—from 14.5% in September 2016 to 16% at the end of 2021—hinting at new activity in non-superstar metro areas. Rising star cities with particularly vibrant growth in hiring ads during the pandemic include Denver and Miami. What’s more, other metro area tech ecosystems beyond the superstars and rising stars—including increasingly dynamic centers such as Phoenix and Houston—have seen increases in their shares of the nation’s tech sector job openings. Such shifts—while only one indicator, albeit a leading one—may well forecast potential adjustments in the geography of hiring and perhaps of the tech sector engaging with remote work and shifting location trends.

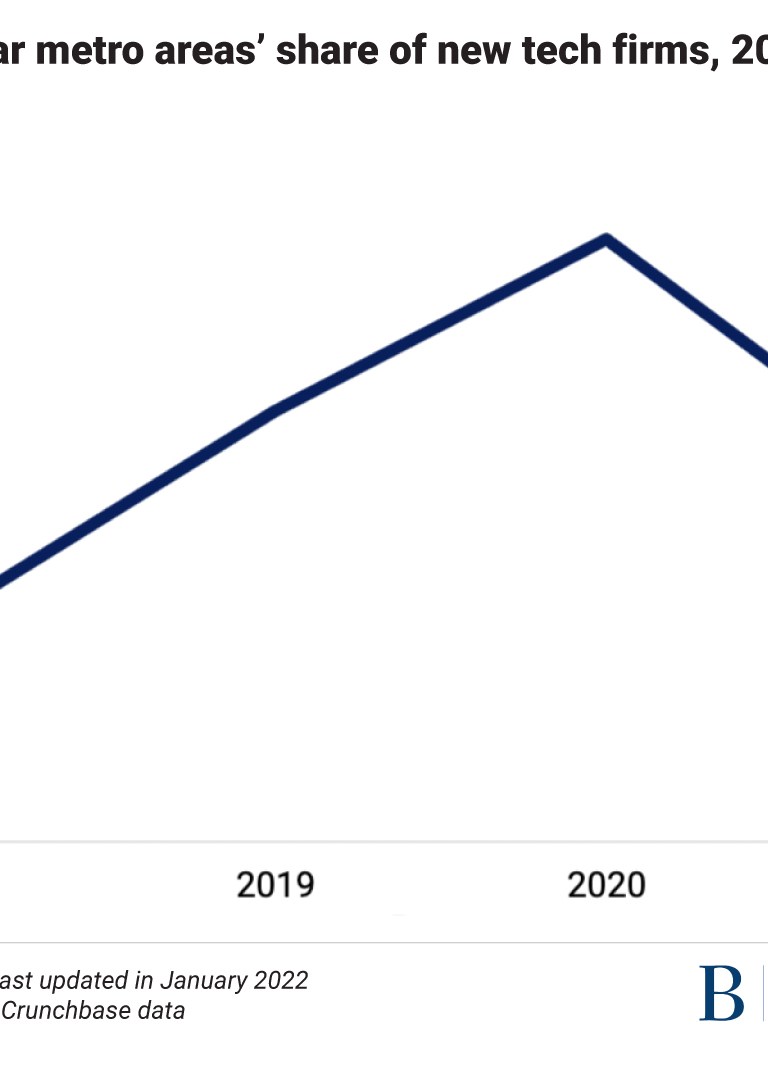

Data on new tech firm starts—available from Crunchbase—corresponds with the job postings trend. After several years of steady increases of tech startup share growth, the eight superstar metro areas’ share of new tech firm starts declined by 2% between 2020 and 2021. Concurrently, the share notched by the rising stars rose 0.4%. Contributing to these shifts were notable startup declines in San Francisco and San Jose, which saw their shares of the nation’s tech startups slip 0.8% and 0.7%, respectively. At the same time, rising star metro area gains on the part of San Diego and Miami pointed to increased vibrancy in those places, as startup share gains ticked up from 1.7% and 3.3%, respectively, to 1.9% and 3.7%.

Also notable was significant growth in Philadelphia’s and Tampa’s shares of the nation’s tech startups, which rose by 1.7% and 0.2%, respectively.

In sum, higher-frequency data extending the analysis beyond 2020 and into 2021 using job postings and startup information reinforces the impression that the pandemic disruption has somewhat—though not massively—reallocated tech activity across cities.

VI. Discussion

The analysis presented here provides a fresh look at tech sector geography at a moment of possible inflection.

Some of the data suggests tech could be on the brink of spreading out, prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic and remote work. Specifically, the continued growth of the rising star metro areas—as well as accelerated job growth in dozens of other metro areas during the pandemic—suggests the possibility of a genuine adjustment of the nation’s highly concentrated tech geography in the coming years. Similar vibrancy outside the most entrenched superstar hubs on measures of hiring activity and new firm starts in tech reinforces this impression.

However, what is equally striking is the persistence of the sector’s superstar geography. Since 2010, the geography of tech has remained highly skewed, with activity and growth concentrated into a short list of large, mostly fast-growing hubs on the West Coast and the Boston-Washington, D.C. corridor. In this regard, what is remarkable is not just that 38.4% of all U.S. tech jobs clustered in just eight of the nation’s metro areas in 2020. Even more noteworthy is the fact that that those metro areas increased their share of the nation’s tech sector employment from 35.2% to 38.2% between 2010 and 2019, and then slightly more amidst the pandemic’s disruptions in 2020.

In short, as recently as 2020, the tech industry remained much more a “winner-take-most” affair than one in which the “rest” of the nation’s tech ecosystems were truly rising, as defined by increasing their shares of the sector’s total nationwide employment.

The question now is whether tech’s slightly more dispersed growth forecasts a shift to greater diffusion, or if it is instead a temporary disruption.

Coming trends that might shift the equation

Several trends discussed here speak to the issue of whether ongoing developments—such as the spread of remote work or the maturation of tech product cycles—are truly beginning to decentralize U.S. tech activity. The answers are ambiguous.

Remote work is garnering the most attention. Such discussions speculate that the pandemic and its aftermath are decentralizing the U.S. tech sector by sending key firm units and the industry’s hottest talent hustling toward the exits of the big, crowded, expensive superstar hubs. And certainly, there are plenty of anecdotes and media stories suggesting that such moves may somewhat shift the nation’s tech geography in the coming years, especially toward smaller tech ecosystems and high-amenity towns.

However, neither the scale of the moves seen to date nor the most frequent format of remote work seem to forecast a wholesale decentralization of tech. First, the numbers don’t really add up, given the still modest flows of people moving out of high-cost metro areas and into “flyover country” (apart from sizable flows out of the Bay Area and New York). Beyond that, recent analyses forecast that, for most knowledge workers, work patterns will be “hybrid” for the foreseeable future, with workers commuting to offices two or three days a week. This level of commuting could limit full exits from established hubs to new locations, though it might well support tech worker shifts to nearby high-amenity satellite towns. With that said, wider-spread acceptance of remote work in the tech sector could, with time, allow greater dispersion of workers and tech activity.

Within-sector technology cycles also merit attention as possible sources of decentralization. Nicholas Bloom’s research on the diffusion of disruptive technologies, for example, builds on economic literature showing that as new technologies mature, a portion of their employment gradually spreads out geographically. Such findings bode well for the spread of more tech employment into new places as portions of the sector mature.

And yet, Bloom’s research (and that of others) underscores that disruptive technologies tend not only to emerge in just a few urban areas—such as the superstar metro areas named here— but also to be commercialized there. Such “pioneer” regions, report Bloom and others, then seem to maintain a persistent advantage in early-stage development and ancillary growth. This, in turn, confers long-lasting local benefits on the early hubs. Given that, the current emergence of new technologies and projects in the sector—ranging from artificial intelligence and quantum computing to AR/VR, Web3, and the metaverse—may well forecast more years of concentration in the established hubs. On this front, too, further diffusion of tech employment into new places appears possible—but so does even more concentration.

Actions that could promote decentralization

What would it take for the U.S. to steer tech into more places and bring greater opportunity to new people and regions? There are several answers.

Some observers will say nothing needs doing. These voices will say the nation’s extreme degree of geographical imbalance is fine, as it reflects the optimal, market-ordained geography for maximizing innovation in a sector heavily shaped by clusters and agglomeration. Alternatively, such observers may say nothing needs doing given the natural diffusion of maturing technology mapped by Bloom and his colleagues. The current spread of remote work has added to this view.

But such confidence in business-as-usual tech trends remains tentative at best, whether among industry veterans, inland entrepreneurs, or heartland economic developers.

Housing and lifestyle crises in the big coastal hubs continue to constitute sizable drags on industry efficiency. At the same time, too many other communities feel that they remain excluded from digital prosperity, as they struggle with underutilization, “brain drain,” and only modest tech growth. What’s more, the self-reinforcing nature of tech sector development underscores the likely rigidity of the current industry structure. As the University of California, Berkeley economist Enrico Moretti has explained, the geography of technology growth is a vexing issue because “initial advantages matter, and the future depends heavily on the past.”

Which is why the pandemic moment is seeing a surge of local and national ferment focused on disrupting—and better balancing—the nation’s deterministic, superstar-dominated tech geography.

There’s no doubt, at the local level, that the remote work experiment during the pandemic has shown that cloud-based tools for workers, firms, and entrepreneurs can open up hopeful prospects for tech activity anywhere. In that vein, urban theorist Richard Florida and economist Adam Ozimek are right that local communities, especially smaller or more remote ones, have an opportunity to “develop their economies based on remote workers so as to try to compete with the big-city business centers and West Coast high-tech meccas that have long dominated the employment landscape.”

So it’s not surprising that numerous communities are taking direct action to attract newcomers with special perks and benefits—some aimed specifically at high-tech workers. Most notable are the cash incentives offered by programs such as Tulsa Remote and Remote Tucson to attract remote workers with cash, perks, or relocation benefits. Savannah, Ga. offered to reimburse relocating technology workers for up to $2,000 of their moving expenses. For its part, the Northwest Arkansas Council offers relocating tech workers $10,000 in cash or bitcoin and a bike.

Yet it remains doubtful that such incentives—offered in limited numbers to the relatively few truly footloose tech workers—will by themselves do much to reverse the winner-take-most nature of America’s economic geography. Such strategies may help some amenity-rich smaller towns generate buzz, but that will not be the case for most communities.

A likely better local strategy for promoting connection will be to focus on the basic block-and-tackling of building out homegrown tech ecosystems that are compelling to firms, entrepreneurs, and workers. This includes the hard work of:

- Building authentic, differentiated tech clusters

- Developing a skilled, abundant, and diverse digital workforce

- Providing excellent broadband connectivity

- Cultivating a vibrant tech community with plentiful networking opportunities and acceleration programs

- Crafting an excellent quality of place, complete with top-notch schools; parks and greenspace; bike lanes; and coworking spaces

Also important for communities is thinking about how to manage the growth that will follow the arrival of hundreds of relocating tech workers who hail from areas that previously struggled with growth-related quality-of-life issues.

In sum, the best way for most cities to promote their own participation in the nation’s tech sector will be to build up the best tech ecosystems and quality of life they can—now and going forward. In that sense, Florida and Ozimek are right that the remote work opportunity could change the focus of smaller cities and towns from luring companies with special deals to luring talent with services and amenities.

Still, given the massive scale of the nation’s tech divides, not even the best of strategies will by themselves be likely to boost local ecosystems enough to democratize the sector’s geography. For that reason, more and more tech leaders, economists, and policymakers are increasingly focused on deliberate efforts to catalyze growth in a limited number of promising new locations in order to disrupt the status quo.

In many parts of the country, renewed state investments in public higher education (after a period of disinvestment) will be necessary in building up new tech hubs. In other regions, the way forward will likely involve complementing existing higher education strengths with coordinated state-level economic development strategies.

Yet not even statewide strategies will likely be sufficient. Federal intervention is also now on the table in a serious way. Specifically, the last few years have seen extensive talk and action in Congress focused on efforts to “seed digital jobs all over the country, even while [ensuring] places like Silicon Valley continue to attract talent and prosper,” as Rep. Ro Khanna (D-Calif.) recently wrote.

Already, 60 finalist regions have been announced in the Build Back Better Regional Challenge, a $1 billion U.S. Economic Development Administration competition that will award 20 to 30 regional coalitions between $25 million and $100 million each to implement projects to drive tech and related cluster development. In addition, pending bipartisan legislation would create a set of large-scale technology hubs to catalyze innovation sector takeoff in a handful of promising inland regions. The Senate’s U.S. Innovation and Competition Act (USICA) and its House companion bill—soon likely to be harmonized in a congressional conference committee—would also boost growth in new regions through new and better place-based and place-conscious investments in technology education as well as the nation’s historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and minority-serving institutions (MSIs). Other initiatives include investments from the National Science Foundation’s artificial intelligence program to catalyze activity in emerging technologies in regions beyond the usual ones. Such programs could deliver a major new place-based innovation surge of the type that once created Silicon Valley and Boston’s tech ecosystem.

In sum, the pandemic years have raised the promise of tech decentralization through remote work and new siting decisions. However, the continued dominance of tech’s long-standing hubs ensures that the “rise of the rest” won’t happen easily, or by itself. The nation, states, and regions themselves will need to help it along.

References

Atkinson, Robert, and Mark Muro. 2019. “The case for growth centers. How to Spread Tech Innovation Across America.” Brookings Institution.

Bloom, Nicholas, and others. 2020. “The geography of new technologies.” Working paper. Institute for New Economic Thinking.

Case, Steve. 2016. The Third Wave: An Entrepreneur’s Vision of the Future.” New York: Simon & Schuster.

Florida, Richard, Andres Rodriguez-Pose, and Michael Storper. 2021. “Cities in a post-COVID world.” Urban Studies. 1-23.

Florida, Richard, and Adam Ozimek. 2021. “How remote work Is reshaping America’s urban geography.” Wall Street Journal. March 5.

Gruber, Jonathan, and Simon Johnson. 2019. Jumpstarting America: How breakthrough science can revive economic growth and the American Dream.

Mims, Chris. 2021. “How working from home can change where innovation happens.” The Wall Street Journal. October 21, 2021

Muro, Mark. 2021. “The geography of AI: What cities will drive the artificial intelligence revolution.” September.

——. 2017. “Tech Is (still) concentrating in the Bay Area: An update on America’s “winner-take-most” economic phenomenon. The Avenue. December 17.

——. 2017. “Tech is divergent.” TechCrunch. March 7.

Mark Muro and Robert Atkinson. 2020. “Countering America’s regional divides is going to take more than hope.” American Enterprise Institute.

O’Mara, Margaret. 2019. The code: Silicon Valley and the remaking of America. Penguin.

Arjun, Ramani, and Nicholas Bloom. 2021. “The donut effect of COVID-19 on cities.” Working paper. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Revolution and Pitchbook. 2021. “Beyond Silicon Valley: Coastal dollars and local investors accelerate early-stage start-up funding across the U.S.”

Acknowledgments

Brookings Metro would like to thank the following for their generous support of this analysis: Dell Technologies, Microsoft, Hillman Family Foundations, Antoine van Agtmael, and Derek Kaufman. The team is also grateful to the Metro Council, a network of business, civic, and philanthropic leaders that provides financial and intellectual support for the program.

The report’s authors would like to thank Alan Berube, Richard Florida, and Margaret O’Mara for providing valuable comments on early versions of the analysis. Jenny Chiang, Emily Laderman, Miguel Liscano, and Carly Tatum provided other forms of support. The authors would also like to thank the following Brookings colleagues for invaluable support in producing the report and contributing to outreach efforts: Dalia Beshir, Michael Gaynor, Annelies Goger, David Lanham, Rob Maxim, and Erin Raftery.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).