Twelve winters ago, as a Wall Street Journal reporter, I spent two dark weeks in Copenhagen covering a round of global-warming negotiations billed as existentially important to the planet. The 2009 Copenhagen climate talks sought to lock down commitments by industrialized countries to bankroll a clean-energy transformation in developing ones. The summit ended as a dud — more chest-thumping by partisans on all sides of the decarbonization debate than an attempt to build a coalition for an environmental transformation.

Since then, however, technology has advanced in ways Copenhagen climate campaigners only dreamed of. For any number of green machines — solar panels, wind turbines, batteries — costs have plummeted and installations have soared. In many parts of the world, studies calculate, installing renewable energy now is cheaper than building coal-fired plants. Renewable energy is ascendant.

There’s just one problem: So, still, are carbon emissions.

Through the end of this week, the movers and shakers of the international economy are gathered at another climate conference, this time in Glasgow. The ambitions have grandly grown; today, governments and corporations are promising, somehow, to slash their emissions to “net zero” by mid-century. Yet the focus in Glasgow remains largely the same as it was in Copenhagen: getting the biggest economies to invest more in clean energy in the countries whose emissions are growing the fastest.

But the history of the past dozen years shows that laboratory progress and overseas investment aren’t enough decarbonize growth in the nations that matter most for the future of the climate — countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, and others beyond Southeast Asia, including in Latin America and Africa. Just as important as gear and cash, and harder to deliver, are workable strategies to rewire these countries’ political economies.

Despite the drop in the cost of cleaner energy, these emerging and developing economies, like the world’s leading economic powers, have failed to meaningfully change their resource-consumption patterns. That’s largely because they have potent sectors and populous regions that sensibly see their interests as yoked to continued and unconstrained carbon output. Offered financing for solar panels and wind turbines, they don’t turn them down. But absent viable futures for their investors and citizens whose livelihoods have long relied on burning fossil fuel, they won’t meaningfully change. Something more foundational has to shift.

To illuminate both that challenge and a way around it, several students at Stanford University, where I teach, and I have spent months harnessing new data to analyze who is calling the carbon-relevant shots in the developing world, and how they’re doing it. Our focus has been infrastructure: the big projects, such as power plants, that will lock in emerging-economy emission trajectories for decades and will thus determine the future of global climate change.

Our findings, published last month in a research article in iScience and explained in a guest essay yesterday in the New York Times, provide new insights into how money is changing the climate. They lay the groundwork for a next stage of inquiry in what we call the Stanford Climate of Infrastructure Project: clarifying why these actors are investing the way they are and how they might be induced to meaningfully change.

Our examination harnesses two sets of data that the World Bank has collected and we have helped bolster. The data includes, for infrastructure projects throughout the developing world, details about which institutions are providing finance, how much they’re providing, and through what financing structures they’re providing it. One of the World Bank data sets has been publicly available for years. The bank provided the other to our Stanford team for analysis and expects to publicly release it by next summer.

Together, these two data sets include approximately 80% of infrastructure projects underway in emerging and developing economies, the World Bank estimates. In other words, it’s a comprehensive look.

As a first pass at the data, we assessed one type of infrastructure: power plants, both because they so significantly dictate future-emission trajectories and because accepted methodologies exist to project, based on this sort of data, long-term power-plant emissions.

Plugging those methodologies into the data led us to some intriguing findings. Some support, with new granularity, long-held assumptions about the carbon pathway of developing-world infrastructure. Others buck those assumptions. Three are particularly noteworthy.

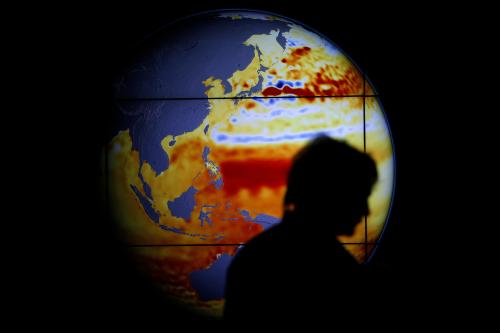

One clarifies the enormity of the climate challenge. We estimate, based on our data, that 52% of the new electricity generation “executed” in emerging economies from 2018 through 2020 is too carbon-intensive to comport with the goal of keeping the average global temperature within 1.5 degrees Celsius of pre-industrial levels. “Executed” is World Bank jargon for having received sufficient financing to proceed. Those three years are the ones the World Bank data allows us to track, but they’re particularly illuminating. They constitute the carbon-intensive status quo — one that many of the governments and corporations now promising to slash their emissions over the next quarter-century have, at least until last year, been quite happy to finance.

Another finding helps clarify why the new infrastructure is so carbon-intensive. Scholarship increasingly has sought to understand the carbon implications of financing for infrastructure in emerging and developing economies; much has focused on coal-fired power plants, because coal is the most carbon-intensive of fossil fuels. But our analysis suggests the focus on coal is increasingly outdated. As institutions finance fewer power plants that run on coal, they are financing ever more that burn natural gas.

We project that, among power plants that were executed in emerging and developing economies from 2018 through 2020 and are in our database, those fired by natural gas will emit 80% as much carbon dioxide over their lives as will those that burn coal. And essentially none of those gas-fired plants are expected, at least anytime soon, to capture and dispose of their carbon emissions. The prevailing tendency to focus on coal as the signal bogeyman in infrastructure development misses the increasingly relevant issue of gas.

A third finding helps to explain the other two — and suggests a way to meaningfully decarbonize infrastructure investment in the developing world by accelerating a transformation of political economies. It rests on the increasing agency of emerging economies themselves in determining the carbon intensity of infrastructure projects built within their borders.

Just as much of the past analysis of the climate impacts of developing-world infrastructure has focused on coal, it has focused on financing from investors overseas — from places, such as China, Japan, South Korea, and the United States, that have extensive domestic industries with interests in selling carbon-intensive equipment and services abroad. But our analysis finds that the emerging economies in which the bulk of global infrastructure is being developed have growing agency over the carbon intensity of that activity.

We find that 44% of electric-generating capacity executed from 2018 through 2020 in emerging economies came not from foreign sources but from domestic ones. Indeed, domestic financiers bankrolled as much new coal and natural gas capacity as foreign financiers did. We also find that, though a given overseas financier tends to fund infrastructure projects of widely differing carbon intensities in different countries, a host country tends to use overseas money for projects of a similar carbon profile.

Both these conclusions suggest that host countries have more power than has been previously recognized to call the shots that will shape climate change.

In one sense, this finding is disillusioning; it indicates that local investors thus far have been no more inclined to go green in a given country than faraway investors have been.

In another sense, though, it offers reason for hope. It shows that domestic institutions could prove a powerful force for decarbonizing infrastructure investment in the nations where the biggest portfolios of those projects are being developed.

Emboldening those domestic institutions to assume that role would require, among other things, policies to cushion the blow to industries and people long reliant on high-carbon endeavors. Effecting this sort of structural change across myriad political economies is a different type of challenge — in some respects, a harder one — than innovating a more-efficient solar panel or persuading an overseas financing institution to send a fatter clean-energy check. But trying to confront climate change without it hasn’t worked.

Since the 2009 Copenhagen climate conference, the cost of renewable energy has cratered, and investment in it has soared. Yet carbon emissions still are on the rise. Realizing today’s promises of net-zero emissions by mid-century will require more than cleaner technology and bigger checks. It will require a more sophisticated capitalism. Molding that new political economy will be messy. And the Glasgow conference doesn’t appear likely to do much about that. As the focus in the climate fight shifts back from Scotland to emerging and developing economies around the globe, policymakers and investors need to get their hands dirty.

Commentary

Infrastructure in the developing world is a planetary furnace. Here’s how to cool it.

November 10, 2021