Overview and main findings

The U.S. economy faces a mobility crisis. After decades of rising inequality, stagnating wages, and a shrinking middle class, many American workers find it harder and harder to get ahead. COVID-19 accentuated a stark divide, battering a two-tiered labor force with millions of low-wage workers lacking job security and benefits—as the long-term trends of globalization, digitalization, and automation continue to displace jobs and disrupt career paths.

To address this crisis and create an economy that works for everyone, policymakers and business leaders must act boldly and urgently. But the challenge of low mobility is complex and driven by many factors, with significant heterogeneity across regions, sectors, and demographic groups. When diagnostics fail to disentangle the complexity, our standard policy responses—centered on education, reskilling, and other reemployment services to help workers adapt—fall short.

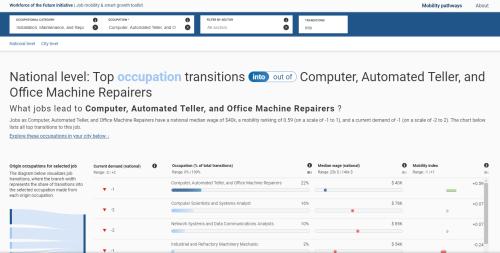

This report offers a new approach to better understand the contours of mobility: Who is falling behind, where, and by how much. Using data on hundreds of thousands of real workers’ occupational transitions, we use network analysis to create a multidimensional map of the labor market, revealing a landscape riddled with mobility gaps and barriers. Workers in low-wage occupations face particular hurdles, and persistent racial and gender disparities hold some workers back more than others.

Even so, many workers travel on pathways to economic mobility. By showing where existing pathways can be expanded and where new ones are needed, this report helps policymakers, community organizations, higher education institutions, and business leaders better understand the challenge of mobility and see where and how to intervene, in order to help more workers move up faster.

The report’s major findings:

1. Mobility gaps exist across wage level, industry, race, and gender

Low-wage industries offer workers less upward mobility. For example, the sector with the lowest median wage, hospitality, also offers its workers the worst prospects for upward mobility. Of all occupational transitions in hospitality, only 36 percent are upward, far from the 66 percent in utilities or professional services, two of the highest paying and most upwardly mobile sectors.

Race and gender mobility gaps hold some workers back. Across the labor market, Hispanic and Black women face the lowest shares of upward transitions: 37 percent and 43 percent, respectively, well below the 57 percent for white men and 61 percent for Asian men. The gaps persist regardless of education: for Asian men with a bachelor’s degree or higher, 75 percent of transitions are upward—compared with only 56 percent for comparably educated Hispanic women.

Industries differ in their mobility gaps. Manufacturing has the largest racial mobility gaps, with Black workers seeing 14 percentage points fewer upward transitions than their white colleagues, and Hispanic workers 18 percentage points fewer. By contrast, mobility gaps are narrower, falling to 6 or fewer percentage points, in government and education, suggesting that public employment may offer more equitable access to mobility

2. Many workers in low-wage occupations get trapped

Low-wage work is sticky. Over 10 years, only 43 percent of workers in low-wage occupations leave low-wage work. Their chances of moving up get smaller and smaller the longer they remain. Every four years, the probability of escaping low-wage work shrinks by half, with the chances reaching only 1 percent in their 10th year.

Traditional pathways from low- to high-wage work are expected to disappear. Steppingstone occupations—middle-wage jobs that have long served as conduits between low- and high-wage occupations—are shrinking as a share of the total employment across the labor market. They made up 16.5 percent of total employment in 2019. According to U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projections for 2029 employment, the labor market will require an additional 775,000 steppingstone jobs to keep their 2019 share of total employment.

Sections of the labor market are like sandpits. In certain occupational categories, workers spend years churning through low-wage jobs, with few prospects for upward mobility. We identify five distinct “sandpit” clusters of the labor market, comprising 37.5 million workers, for whom only 38 percent of transitions are upward.

3. While pathways exist, they are narrow and full of hurdles

Workers move in well-defined patterns. Using network analysis, we identify 15 distinct occupational clusters that have stark differences in wages and mobility. Workers move within these boundaries far more frequently than they cross them: Transitions involving occupations in the same cluster are 3.8 times likelier than cross-cluster transitions.

The 4.3 million workers in the assemblers and machine operators sandpit cluster, who are especially vulnerable to job displacement and technological disruption, need new pathways out. After factoring in the effects of COVID-19, the BLS projects the cluster will lose as many as 301,000 jobs, a 7 percent drop. Moreover, 21 of the cluster’s 26 occupations are expected to contract. Whereas these occupations would have been natural landing places for displaced workers, many workers will need to find reemployment outside their cluster, a much more difficult task.

For workers trapped in low-wage sandpits, skyway occupations offer lifelines. To escape occupations with low wages and low mobility prospects, some workers must make a cross-cluster leap to a new, more promising area of the labor market. While this is always challenging, some occupations are like skyways, connecting sections of the labor market. They are as varied as jobs in construction or information technology (IT) support, but they all have low barriers to entry and plentiful opportunities for career development.

Pathways to high-wage work exist, but access is unequal. For example, the health care cluster, which accounts for 34 percent of the labor market’s total projected job growth over the next decade, offers notable opportunities for mobility due to existence of both high- and low-wage jobs, with pathways between them. Even so, many upward pathways are marked by gender and racial barriers: white licensed practical nurses (LPNs) are more likely to transition upward into registered nurse (RN) positions, while Black and Hispanic LPNs are more likely to transition downward into lower-wage jobs in home health and personal care.

4. Refining policy targets can help more workers move up

Jobs programs, infrastructure investments, targeted training, wage subsidies, portable benefits, and public–private reskilling programs can leverage occupational transitions analysis to identify workers’ viable opportunities, feasible pathways, and thus the highly-valued credentials that those transitions require.

Companies, meanwhile, can do more to unlock bottlenecks. They can measure the mobility of their workforce, identify and address any gaps or barriers, create good jobs, and expand mobility opportunities for their employees.

Workers in sandpit clusters need better wages and benefits. Ensuring that employment in low-wage occupations entails adequate compensation—stability, living wages, and minimum benefits—would do much to improve most low-wage workers’ mobility prospects by offering a much-needed buffer to workers interested in pursuing new skills training, education, or entrepreneurship. And to the many working people who will not advance, adequate compensation ensures the opportunity to thrive in American society.