This brief is part of a five-part series examining how downtown commercial corridor revitalization can support rural recovery and resilience, and the policy and capacity-building supports needed to enhance and scale these strategies amid the COVID-19 crisis and beyond.

Contents

- I. Introduction

- II. Rural America is changing, and rural economic development must change too

- III. How we examined downtown revitalization as a locally led strategy to build rural resilience

- IV. Conclusion

Introduction

After months of dispersion throughout the northeast and southern United States, COVID-19 outbreaks are concentrating in rural areas this fall, surging in remote, sparsely populated towns and inflicting a disproportionate toll on the communities of color within them. Alongside this rural surge comes the doomsday queries: Will rural America—with its limited health care infrastructure and high-risk industries—be able survive the regional COVID-19 storm? Can rural small businesses—the lifeline of many rural towns—withstand the economic toll? What will happen if our nation’s Main Streets turn into ghost towns?

These concerns are not unfounded. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, rural1 and small towns were already facing a precarious economic future. Many have not yet regained the employment levels they had prior to the Great Recession, face disproportionately high poverty rates, struggle with depopulation, and lack the critical infrastructure (such as broadband access) needed for economic growth. Their economic precarity has grown more dire amid the extended devastation of COVID-19, and is exacerbated by an uneven small business crisis hitting leisure, hospitality, and recreation-based businesses particularly hard. Moreover, as is the case in cities and towns across the nation, the pandemic’s toll is disproportionately impacting the rural residents, workers, and businesses that were already vulnerable before the crisis, particularly Black, Latino or Hispanic, and Native American residents, low-wage workers exposed to substandard working conditions in meatpacking plants and prisons, and locally owned small businesses with limited access to capital.

The heightened economic vulnerability of rural communities has garnered significant attention in recent months, prompting many to call for concentrated fiscal relief to help rural residents, small businesses, and state and local governments weather the COVID-19 crisis. Yet alongside this call, some scholars, including our Brookings colleagues and others, argue that to lay the groundwork for true rural resilience and chart a more equitable recovery trajectory than the previous one, rural economic development policy requires a fundamental shift—one that recognizes the vast diversity of rural America and invests in local strategies that strengthen community assets and bolster local leadership to promote truly resilient economic opportunity.

This shift undoubtedly requires support at the federal, state, and local levels. It also demands that we look deeply at—and invest in—homegrown rural economic development strategies that were showing promise prior to the pandemic. As we demonstrate in this five-part series, locally led rural downtown revitalization efforts have the potential to be one such strategy.

Indeed, some rural communities achieved economic revival in recent years by concentrating and investing in community assets in downtown commercial corridors, with the goal of supporting a cluster of locally owned small businesses, fostering an accessible entrepreneurial ecosystem, improving the quality of life, and promoting an inclusive sense of place that retains and attracts residents. In partnership with Main Street programs and other place governance organizations, these downtown revitalization strategies are street-level solutions rooted in local contexts, based in community strengths, and led by a coalition of local leaders and organizations dedicated to enhancing economic opportunity for rural residents. Now, as COVID-19 further exposes the economic instability of rural areas and, in particular, rural small businesses, the viability of these strategies is being tested in real time.

To better understand the effectiveness of rural downtown revitalization efforts heading into the COVID-19 recession—and the role they might play in a contemporary strategy for rural recovery and resilience—this series uses on-the-ground research in three rural communities from just prior to the COVID-19 outbreak in the U.S. and examines how downtown revival impacts four holistic indicators of community well-being. Centering the perspectives of rural residents, business owners, and community leaders, we investigate three central questions: 1) Whether downtown revitalization efforts have been successful at enhancing economic, built environment, social, and civic outcomes prior to the pandemic; 2) whether pre-pandemic revitalization efforts are helping rural small businesses more durably weather the COVID-19 crisis now; and 3) what further policy and capacity-building supports are needed to ensure rural Main Streets not only survive the pandemic, but can be leveraged as key strategies to promote rural recovery and long-term resilience.

|

Methods: How we examined downtown revitalization in rural America

The Brookings Bass Center for Transformative Placemaking and the National Main Street Center partnered to conduct in-depth, on-the-ground research in three rural communities across the United States between February and March 2020: Emporia, Kan.; Wheeling, W.Va.; and Laramie, Wyo. We chose qualitative research as our primary mode of investigation (with supplemental quantitative analysis), as we were interested in holistic outcomes (e.g., entrepreneurial innovation, perceptions of inclusion, and quality-of-life concerns) that numbers alone cannot adequately capture. Moreover, we wanted to identify tangible strategies and lessons for the field directly from rural small business owners, public officials, and residents.

Our on-the-ground data collection activities consisted of in-depth individual interviews with 62 residents, business owners, and other key stakeholders, as well as four supplemental focus groups with residents and entrepreneurs. We began in-person data collection just prior to the COVID-19 outbreak in the United States, and therefore conducted in-person, weeklong site visits in Wheeling and Laramie, but switched to virtual interviews for Emporia due to COVID-19 travel restrictions. We analyzed respondents’ insights based on four key outcomes of community well-being as defined in the Bass Center’s transformative placemaking framework, examining whether rural downtown revitalization efforts were successful in:

1. Nurturing an economic ecosystem that is regionally connected, innovative, and rooted in the assets of its local residents and businesses. 2. Supporting a built environment that is accessible, flexible, and advances community health and resiliency. 3. Fostering a vibrant, cohesive social environment that is reflective of community history and identity. 4. Encouraging civic structures that are locally organized, inclusive, and support network building.

We then conducted supplemental quantitative analysis on each of these outcomes, using Census Bureau, Esri Business Analyst, and local data when available. Each brief in the series presents in-depth findings related to one of the four key outcomes. |

II. Rural America is changing, and rural economic development must change too

Despite increased attention paid to rural towns as “left behind” and the renewed urgency to support them through the COVID-19 pandemic, mainstream perceptions of rural America—and the policy interventions that accompany them—tend to cling to an outdated image of homogenous rural small towns. Yet, as a recent Center for American Progress report demonstrates, rural communities are remarkably diverse, and not as white, dependent on extractive industry, or defined by challenges as many portrayals presume. Given these realities, there are three primary truths that any rural revitalization strategy—including federal, state, and local interventions—must keep in mind:

- Rural communities increasingly rely on demographic diversity for population and economic growth. People of color comprise 21% of the total rural population, with a sizeable Black population in the rural Southeast and sizeable Native American and Latino or Hispanic populations in the Great Plains and Southwest. People of color are critical to the success of rural areas, as they generated 83% of rural population growth between 2000 and 2010. They have continued to drive population growth in the years since, particularly Latino or Hispanic migration in depopulating parts of the rural Midwest.

- Rural communities possess unique local assets that require locally tailored investment strategies. Despite often being characterized by deficits, rural communities possess a diverse array of local assets—from social infrastructure to natural resources to local innovation—that can be leveraged to support locally tailored revitalization strategies. In many rural communities, place-based organizations have long been engaged in efforts to strengthen these local assets for economic development and community revitalization.

- Rural economies vary considerably, but increasingly rely on a strong small business and entrepreneurial ecosystem. Economic prosperity varies considerably across rural areas, and depends significantly on the dominant industry in the region (e.g., recreation, manufacturing, agriculture, etc.). Agriculture employs less than 5% of the rural workforce, and manufacturing employs only 15%. Small businesses, on the other hand, provide the majority of jobs in rural economies (Figure 1), particularly in recreation, leisure, and hospitality In the economic development field, there has been growing recognition that traditional industry cannot save rural America. Fostering an ecosystem for small businesses and entrepreneurship can be a critical alternative to declining industries, alongside efforts to enhance digital skills and economic dynamism in rural places.

Given the vast economic, demographic, and regional differences across rural America—and the unique assets and challenges rural communities possess—the imperative to advance locally tailored economic development strategies is clear. Indeed, downtown revitalization is one locally led alternative to more traditional economic development approaches that strive to attract large employers and industries. Yet despite the widespread adoption of downtown revitalization, relatively little is known about its effectiveness in promoting holistic community well-being, and even less is known about how rural downtowns might withstand acute crisis.

The three research communities

To understand the promise of downtown revitalization in promoting a resilient rural America, we jointly selected three research communities from which to directly engage residents, business owners, public officials, and other community leaders. We selected communities based on the following criteria: 1) Whether they were engaged in an ongoing downtown/Main Street revitalization effort with a sufficient amount of time to have demonstrated impact; 2) whether the rural town was significant to its broader regional economy; and 3) whether their revitalization strategies could be replicable to a diverse array of rural communities. The three communities we chose were:

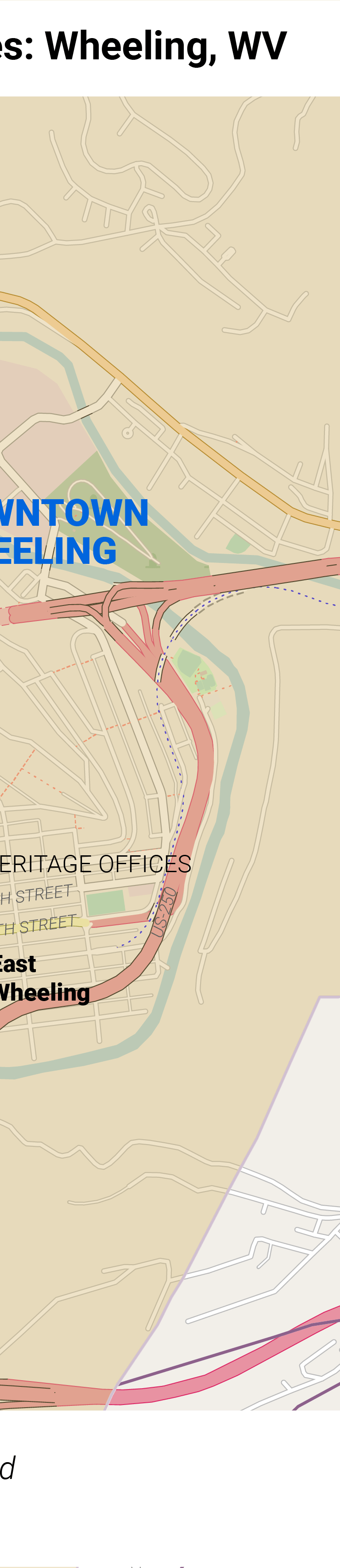

1. Wheeling, W.Va.: Located along the Ohio River, Wheeling’s manufacturing sector and prime location made it West Virginia’s industrial center after the Civil War. In the 1980s and 1990s, however, Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel reduced its employment, retailers began to leave Wheeling for the suburbs, and disinvestment and population loss caused socioeconomic decline. In 2018, Wheeling had a population of 27,000—down from 48,000 in 1970. When Wheeling Heritage, a nonprofit organization located in Wheeling, launched a Main Street program in 2015, the downtown’s vacancy rate stood at 32%. Today, Wheeling Heritage has an annual operating budget of about $1.3 million, with seven full-time and two part-time staff. Their downtown revitalization efforts have centered on leveraging historic assets and industrial history, creating a robust entrepreneurship support system to create local businesses, supporting a downtown shopping, dining, and arts scene, and transforming a warehouse and former department store into multifamily market rate apartments.

2. Laramie, Wyo.: Located in southeastern Wyoming, Laramie became a frontier town with the arrival of the Union Pacific railway in the late 1800s. Its contemporary economy is largely dependent on the University of Wyoming (located in the city’s eastern half), and the city’s retail and health sectors. Unlike many rural areas, Laramie has witnessed positive population growth in recent years, and was home to 32,000 residents in 2018—up from 29,000 in 2010. Nevertheless, Laramie is still one of the poorest communities per capita in Wyoming. Launched in 2005, the Laramie Main Street Alliance’s downtown revitalization efforts have focused on enhancing Laramie’s historic district, driving growth in small business creation and employment, adding downtown housing, supporting a downtown mural project, and hosting community events such as art walks and farmers markets. More recently, the Laramie Main Street program launched a partnership with the University of Wyoming’s entrepreneurship program to provide training to downtown businesses, and is introducing a “Made on Main” program aimed at placing small manufacturers and producers in vacant downtown spaces. In 2019, the Laramie Main Street Alliance had an operating budget of about $230,000 and employed two full-time and three part-time staff members.

3. Emporia, Kan.: Located in the Flint Hills of East Central Kansas, Emporia first emerged as a major railroad hub along the Union Pacific’s Southern Branch after the Civil War. Emporia sits along Interstate 35, the major north-south corridor from Texas to Minnesota. Emporia’s core downtown district resides at the intersection of State Highway 99 and Federal Highway 50, with Interstate 35 just a few blocks away. Emporia is home to a Tyson Foods meat-processing plant, which has become a site of vulnerability amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Emporia’s population has declined slightly in recent years, standing at 24,000 residents (down from 26,000 in 2010). The downtown is anchored at one end by Emporia State University, while the Lyon County Public Transportation System (LCAT) and city and county government offices are located downtown, with most of the city’s community entertainment and athletic venues located in or adjacent to the core area. Emporia has been using the Main Street Approach for 26 years, and in that time, their work has centered on local economic development programs (including zero interest loan programs, tax credits, and other financial vehicles) to support startups and business expansions, as well as efforts to increase market rate housing downtown and create incubation spaces for aspiring entrepreneurs. Emporia Main Street has an annual operating budget of about $250,000 and employs two full-time staff members.

|

III. Examining downtown revitalization as a locally led strategy to build rural resilience

Research clearly demonstrates the benefits of urban downtowns, indicating that density and proximity to people, jobs, and amenities can fuel population and economic growth in the nation’s biggest metro areas. But we don’t know how these findings translate to micropolitan areas, or whether rural downtowns might achieve similar benefits through residential and business density relative to surrounding areas (Figures 3 and 4).

For decades, local leaders, community development organizations, and Main Street programs have engaged in efforts to leverage this density to cultivate rural downtowns as vibrant “regional hubs” that foster locally owned businesses, create employment centers for residents, and contribute to a sense of place that retains residents and attracts new ones. Despite this widespread adoption, research on rural downtown revitalization is limited and mostly descriptive, often using surveys administered through the Main Street network, for instance, to report on the number of buildings rehabilitated, number of people that attend events, and public and private spending invested downtown. The research base for Main Street communities in particular often centers on procedural considerations and built environment improvements, indicating that downtown revitalization shows promise for building rehabilitations and historic preservation efforts. However, we lack a broader understanding of whether downtown revitalization can produce more holistic, inclusive outcomes in rural communities—and, moreover, how these outcomes may shift and adapt amid today’s economic crisis.

To fill this gap, this research series takes a mixed-methods approach to evaluating rural downtown revitalization, interrogating the pressing concerns facing rural areas amid the COVID-19 economic crisis and looking ahead at the capacity-building supports needed to maintain momentum in the future. To this end, each of the four subsequent briefs in the series tackles one key set of questions about the role rural downtown revitalization may play in promoting rural recovery and resilience, including:

- Can downtown revitalization help rural small businesses more durably recover from the crisis and build resilience in the long term? Rural small businesses were already facing systemic disadvantages heading into this recession. Having not yet recovered from the Great Recession, they face diminished access to capital and are increasingly vulnerable to fluctuations in tourism and recreation—industries that COVID-19 has devastated. Our brief, “Rural small businesses need local solutions to survive” interrogates the roles that downtown revitalization efforts—and the place governance structures that support them—are playing in nurturing a locally empowering and resilient ecosystem for small business survival, growth, and development.

- Can downtown revitalization support built environment and quality-of-life improvements that benefit underserved rural residents and small businesses amid this economic crisis and beyond? Rural communities are challenged by significant built environment and infrastructure needs that act as persistent barriers for residents and small businesses and render them disconnected from broader markets. Moreover, many rural communities face aging building stock, gaps in access to grocery stores and other amenities, and automobile-focused development that makes transportation difficult without a car. This has direct implications for quality of life in rural areas and disproportionately impacts Black and Native American residents, who consistently report lower quality of life than their white peers. “The necessary foundations for rural resilience: A flexible, accessible, and healthy built environment” investigates whether downtown revitalization efforts are promoting the built environment and quality-of-life improvements needed to contribute to health and resilience for a broader swath of rural residents.

- Can downtown revitalization strengthen and diversify the social cohesion and strong attachments to place needed to maintain inclusion and resilience in rural America? Many rural and small towns were grappling with depopulation prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and relied on growing demographic diversity—particularly Latino or Hispanic migration—to spur revitalization. Now, as COVID-19 threatens economic opportunity in rural areas and magnifies long-standing divisions by race, ethnicity, and income, their ability to remain places where people want to live and stay is at risk. “Rural Main Streets can’t achieve true economic revival without bridging social divides” examines whether downtown revitalization efforts are fostering cohesive social environments that nurture racial and economic inclusion, reflect community identity, and enhance residents’ attachments to place.

- Can downtown revitalization support the development and capacity of community-based organizations, coalitions, and networks to build rural resilience? While place-based organizations and other civic groups have stepped in to provide services in rural communities in absence of other supports, significant gaps in local organizational capacity persist. Moreover, access to civic representation at the community level is often uneven, with Latino or Hispanic immigrants, in particular, facing great challenges with existing systems of governance and traditional participatory mechanisms like public meetings. Finally, community-based development efforts in rural areas are often isolated from regional economic development strategies, which can harm both people living in rural communities as well as broader regional economies. “Creating a shared vision of rural resilience through community-led civic structures” examines whether downtown revitalization efforts are nurturing civic structures that enhance local capacity, ensuring an inclusive process for community participation, and connecting efforts to regional strategies.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that rural downtown revitalization—when anchored by strong place governance structures, deep knowledge of community priorities, and robust public and private partnerships—are critical homegrown solutions for building rural resilience. The stakes are high for acting upon these insights and scaling these locally led efforts amid the COVID-19 economic crisis. The last recession deepened our nation’s socioeconomic rifts to devastating effect. Geographic inequities in community health and well-being are not just a dire concern for those living in rural and small towns; they are an alarming indicator of rising national inequity, which denies millions of people the chance for opportunity simply because they live in the “wrong” places.

As we plan to recover from the COVID-19 economic crisis, we must intentionally prioritize regional equity, recognize the spatial interdependence of rural and urban areas’ shared economic future, and invest in the hyperlocal support systems already working to bring growth and equity to rural areas. To truly recover as a nation, we must embrace a bottom-up paradigm for development that empowers rural communities to tackle these place-based inequities and foster inclusive, vibrant, and connected places in the long term.

The authors thank Joanne Kim, D.W. Rowlands, and Evan Farrar for their research assistance.

-

Footnotes

- Defining “rural”: Researchers and policymakers disagree on what constitutes a “rural” area, with many using the definition of “nonmetropolitan” interchangeably with rural. This paper uses the nonmetropolitan delineation; however, it recognizes that there is no simple rural-urban dichotomy, nor are such dichotomies necessarily useful. Binary classifications shift over time due to changes in population, may fail to capture cultural understandings of “rural” that do not reflect demographic data, and may serve to obscure the interconnected nature of rural-urban interdependence in today’s economy (Dabson, 2019; Ajilore and Willingham, 2017; Lichter and Ziliak, 2017).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).