Every person deserves the opportunity for dignified employment that provides living wages and potential for advancement. But for many in America today caught in a cycle of low-wage work, this is far from reality.

Low-wage workers are struggling—and not for a lack of new jobs. The coming flood of innovation will create new tasks and occupations, and the labor market will demand new skills just as quickly as it will shirk others. Robots may be unlikely to wholly replace America’s workers anytime soon, but new technologies will radically displace workers, eliminating jobs in some industries while expanding others.

Policy and company responses have failed to keep pace with this transformation. As the labor market splits into low-wage and high-wage work, lower tier jobs are precarious, marked by unpredictable schedules, reduced benefits, and stagnant wages. While reskilling alone will not be enough to lessen inequality or provide equal opportunity in the face of these trends, it must be an integral part of the solution to support workers without leaving anyone behind.

This new research leverages data to highlight the realities of low-wage work in America and maps realistic pathways to mobility. We examine how labor market dynamics shape the way low-wage workers move within and between occupations and develop a near-term mobility index that estimates whether workers will earn more money by transitioning out of certain occupations. We pair this index with projections of local occupational growth to show how city planners can invest in key industries and design programs that provide workers with realistic opportunities for upward transitions.

Who are America’s most vulnerable workers, and what are their prospects?

An estimated 53 million people—44 percent of all U.S. workers ages 18–64—are low-wage workers. That’s more than twice the number of people in the 10 most populous U.S. cities combined. Their median hourly wage is $10.22, and their median annual earnings are $17,950.

Low-wage work spans gender, race, and geography, but, women and members of racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately likely to be low-wage workers. A Black worker is 32 percent more likely to earn low wages than a white counterpart—that number jumps to 41 percent for Hispanic workers. Altogether, women are 19 percent more likely than men to be low-wage workers.

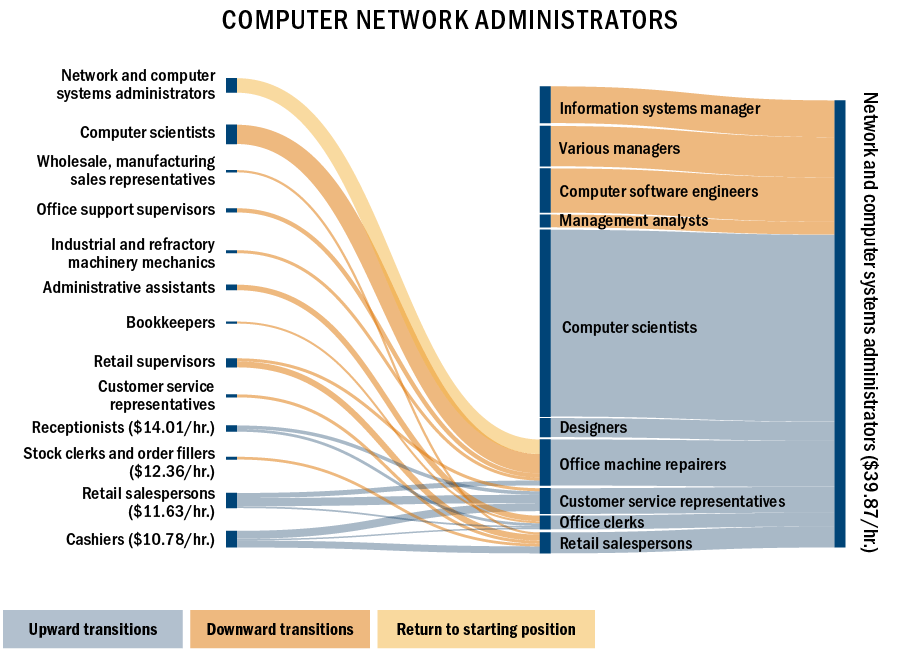

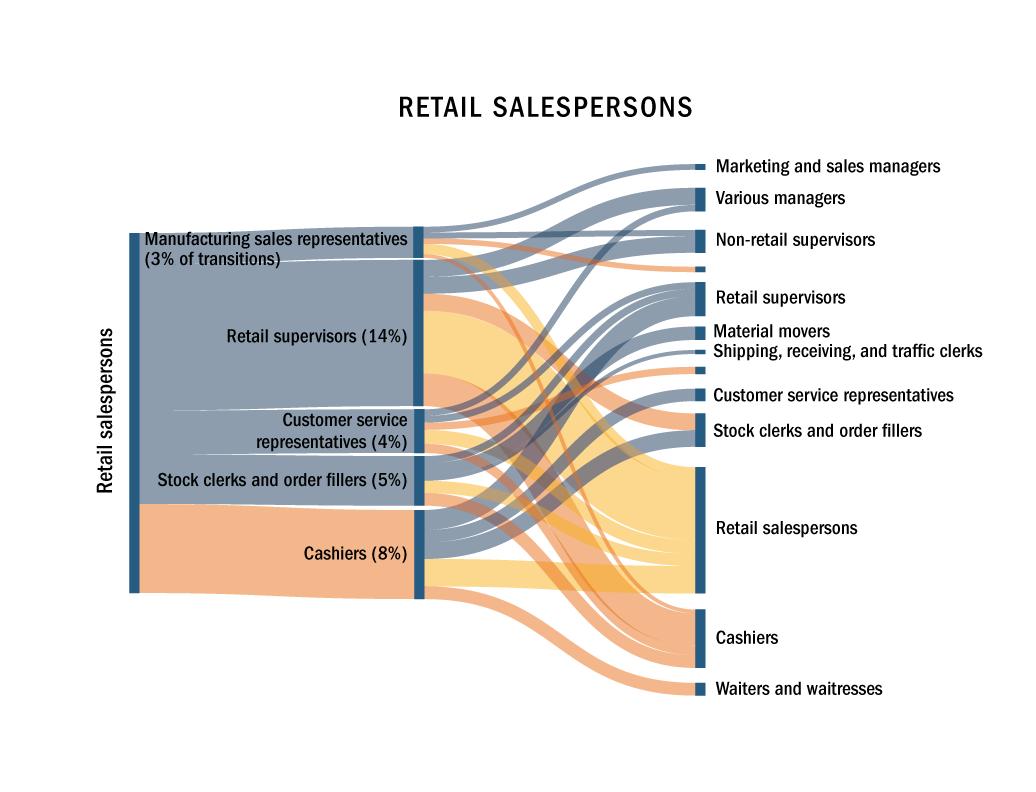

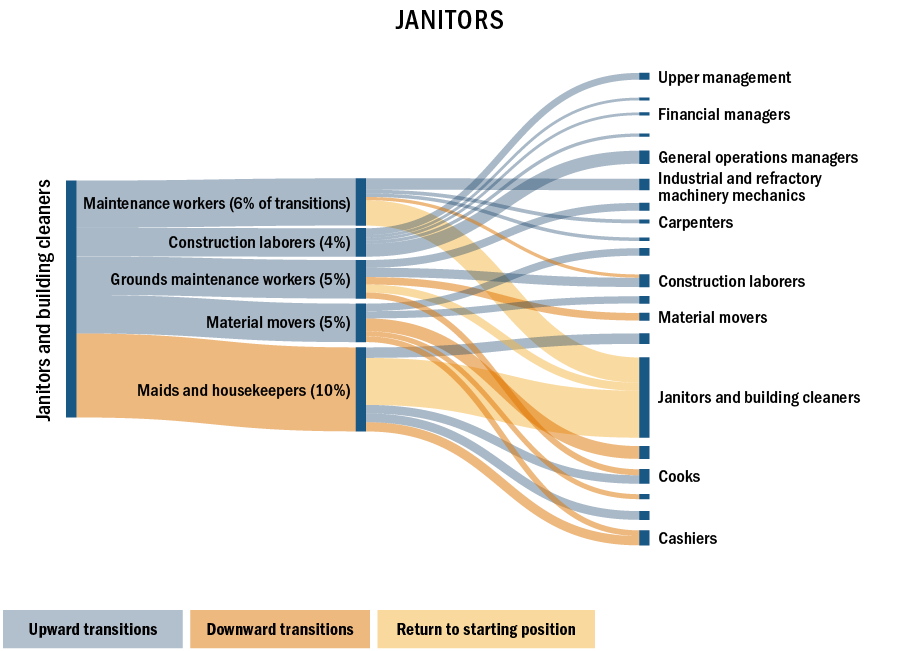

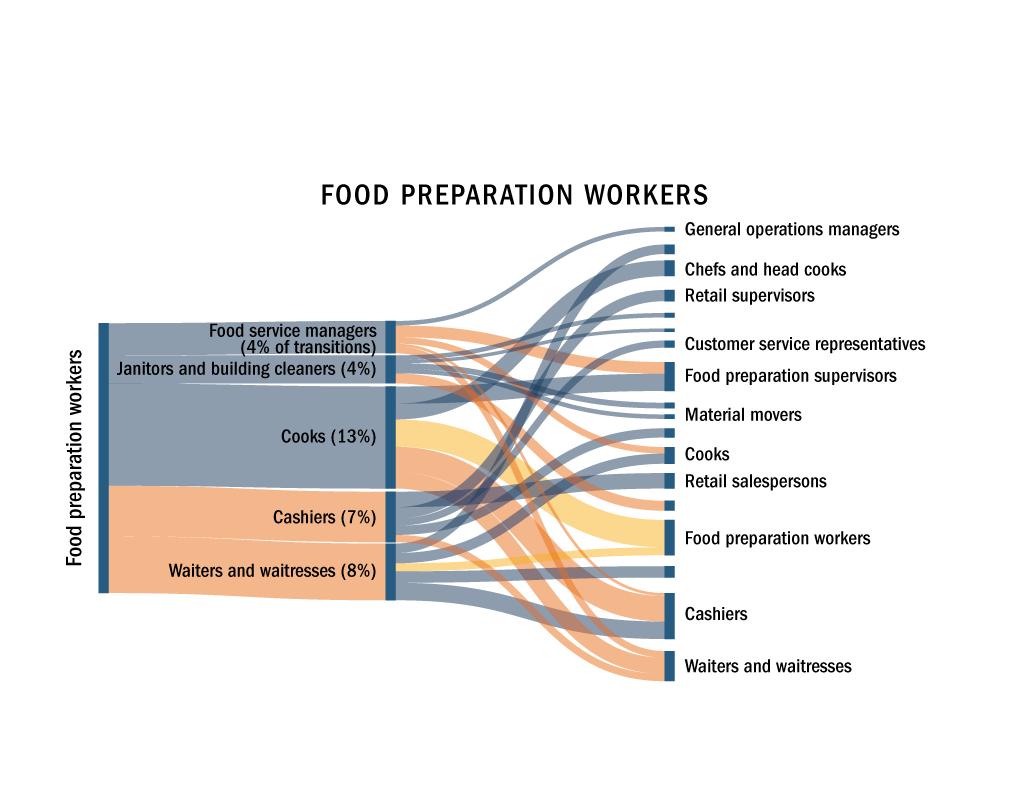

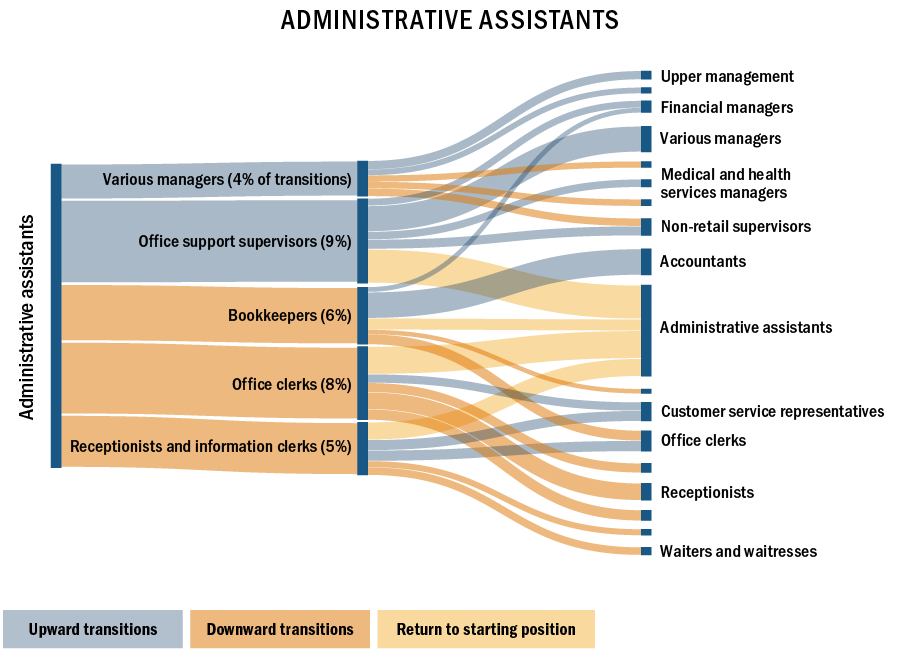

Low-wage workers switch jobs most frequently but are more likely to churn within a set of low-wage occupations. Workers in the lowest wage quintile have the highest likelihood to switch into another low paying job. Workers in the second lowest quintile have a 55% chance to remain or move downward, and even those in the middle quintile are more likely to move to a lower wage group than a higher one.

Certain occupations are likelier to lead to higher wages. Our near-term mobility index estimates whether workers departing an occupation are likely to see higher wages. For instance, telemarketers tend to transition to a much higher paid job, compared to cooks or housekeepers. Cleaners, cooks and hairdressers, are the most vulnerable; their occupations pay low wages and offer little opportunity for advancement.

Where are the local opportunities for mobility, and how can policymakers help low-wage workers transition?

Because complex industries can potentially drive growth and bring the unemployed and underemployed into the workforce, city leaders should deliberately cultivate the capabilities needed to host (and attract) strategic industries. Our previous report, Growing cities that work for all, describes how cities might identify those strategic industries. But urban policymakers must balance the need to host high-wage industries with efforts to support low-wage workers by increasing living wages, improving job quality, and expanding access to housing, transportation, and upskilling. The two sets of policies—to promote both growth and inclusion—are complementary, but they require distinct efforts.

Comprehensive local strategies must link industrial and workforce development. Workforce development is most promising when tied to specific economic development strategies. Cities facing job losses might combat the path-dependence of industrial trends by making strategic investments in industries that build on regional capabilities and also bring good jobs. Place-specific insights on the growth and decline of occupations, and the opportunities it create for low wage workers, can help policymakers and firms build a reskilling infrastructure that brings opportunity to those who need it the most.

A data-driven roadmap for city-level industry and workforce planning

1. Do local industries have the potential to grow?

Regions can think strategically about the industries they foster to promote growth and inclusion. Cities can build capabilities to host industries that not only drive growth, but also offer good jobs for their workers.

2. What are cities’ workforce needs?

Global trends drive local workforce needs. But local industry structure also determines the regional demand for talent. Low- and high-wage jobs will be created and lost, and these will vary by city. Policymakers can use place specific occupational projections to help build the human capital that advanced industries seek.

3. Which workers are best able to transition and what avenues exist for low-wage workers?

4. How can we help workers reskill?

Skilling, if connected to local opportunity, can be an engine for mobility. To promote mobility, reskilling infrastructure can target destination occupations that are expected to grow, likely to offer higher wages, and are realistic, given a worker’s starting occupation or employment history. To be inclusive, skilling programs need to meet workers where they are.

![]()

5. How can public-private collaboration support workers?

Armed with this information, policymakers can design reskilling programs that tap into local talent pools and facilitate workers’ realistic upward transitions into growing occupations.

Findings from this report can be applied to:

• Provide policymakers with a window into the forces driving the local and national proliferation of low-wage work.

• Illuminate upward transitions available to workers and facilitate strategies that link industrial policy and reskilling efforts to drive inclusive growth.

• Assist workforce development practitioners as they design programs to meet workers where they are.

Read the companion report titled “Meet the low-wage workforce” by Martha Ross and Nicole Bateman.

Note: Carlos Daboin, Brody Viney, Ceylan Oymak, Kaitlyn Steinhiser, Natalie Geismar, and Isha Shah provided invaluable research, visualization, and analytical help and continue to work on the online visualizations that will accompany this work. Jose Ramon Morales provided advice in industrial development and econometrics. Peter DeWan, as an integral member of our research team, contributed his expertise on network-based analysis to develop the mobility metrics, which will continue to drive our research on mobility.