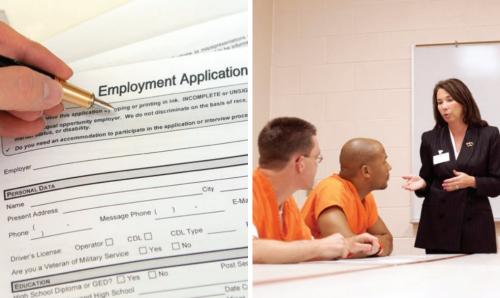

Two-thirds of those released from prison are re-arrested within three years. This incarceration cycle hurts families and communities—and also costs a lot of money. Governments and nonprofits have tried many programs to reduce recidivism, but most are not successful. In a recent review of the literature on prisoner reentry, I summarized the best evidence on how to improve the lives of the formerly incarcerated. One of the most striking findings was that reducing the intensity of community supervision for those on probation or parole is a highly cost-effective strategy. Several studies of excellent quality and using a variety of interventions and methods all found that we could maintain public safety and possibly even improve it with less supervision—that is, fewer rules about how individuals must spend their time and less enforcement of those rules. Less supervision is less expensive, so we could achieve the same or better outcomes for less money.

For instance, Hennigan, et al. (2010), measured the effects of intensive supervision using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Los Angeles. Juveniles sentenced to probation were randomly assigned to intensive supervision—in the form of a community-based after-school program—or standard probation. Five years later, there were no significant differences in outcomes between the treatment and control groups, with one exception: Low-risk boys (ages 15 or younger) who were randomized to intensive supervision were worse off. Intensive supervision for that group led to more incarceration and a higher likelihood of continued criminal justice involvement in the years ahead. That is, intensive supervision increased criminal activity by this group, without reducing criminal activity by other groups.

Barnes, et al. (2012) used an RCT to study supervision levels in Philadelphia. Low-risk probationers were randomized to probation as usual or low-intensity supervision by parole officers with high caseloads (which forced them to pay less attention to each individual case). Less supervision means probationers may be less likely to get caught for technical violations, such as using drugs or breaking curfew. But these requirements of probation are a means to an end: what really matters for public safety is the number of new offenses committed. Eighteen months after randomization, there were no significant differences between the treatment and control groups in the likelihood of being charged for a new offense. In other words, low-intensity supervision did not result in more recidivism.

Boyle, et al. (2013) evaluated the effects of Day Reporting Centers (DRC) using an RCT in New Jersey. High-risk parolees were randomly assigned to either a DRC or parole supervision as usual. Those assigned to a DRC were required to attend programming at the DRC every weekday and submit to regular drug testing. The hope was that reporting to the DRC until they had something else to do during the day (work or school) would keep parolees out of trouble. The DRC provided a variety of services designed to facilitate successful reentry. Nonetheless, those assigned to a DRC instead of regular parole were actually more likely to be convicted for a new offense in the 6 months after their release. After 18 months there was no significant difference in recidivism between the treatment and control groups. Those at the DRC did not do better than those on standard parole, despite the many services available. The authors hypothesize that being required to spend weekdays with other recently-released offenders may impose negative peer effects that are actively counterproductive.

Georgiou (2014) used a natural experiment to measure the effects of supervision levels for parolees in Washington state. Before release, inmates are assigned risk scores, and those risk scores correspond to risk categories that determine the level of supervision they receive: for instance, scores of 1-5 might be “low risk” while 6-10 is “moderate risk” and 11-15 is “high risk.” Two individuals with similar risk scores might receive very different levels of supervision if their scores are on either side of a risk category cutoff —in this example, 5 vs. 6 or 10 vs. 11. Georgiou confirmed that in this dataset, when an offender has a risk score just over a cutoff, this caused a big increase in the hours of supervision they received. If intensity of supervision matters, then this big difference in supervision levels should affect recidivism. However, those big increases in supervision did not have any effect on the likelihood of a new conviction during the three years after release, at any of the risk thresholds examined.

Finally, Hyatt and Barnes (2017) examined the effectiveness of intensive supervision using a particularly impressive RCT in Philadelphia. High-risk probationers were randomly assigned “moderate risk” or “high risk” labels that determined the actual level of supervision they received. That is, their label did not correspond at all to their actual risk level. Neither the probation officers or the offenders knew about this experiment; they interpreted the labels as valid. One year after assignment, there was no significant difference between the two groups in new charges or days incarcerated. Those assigned to intensive supervision did have more technical violations, evidence that that they were caught breaking rules that were supposed to keep them out of trouble. But those rules, and the intensive supervision to enforce them, produced no public safety benefit to community members.

These studies show that current efforts to reduce recidivism through intensive supervision are not working. Why is intensive supervision so ineffective? Requiring lots of meetings, drug tests, and so on can complicate a client’s life, making it more difficult to get to work or school or care for family members (meetings are often scheduled at inconvenient times and may be far away). A heavy tether to the criminal justice system can also make it difficult for individuals to move on, psychologically. Knowing that society still considers you a criminal may make it harder to move past that phase of your life. These difficulties may negate the valuable support that probation and parole officers can provide by connecting clients to services and stepping in to help at the first sign of trouble.

It is unclear what the optimal level of supervision is for those on parole or probation, but these studies demonstrate that current supervision levels are too high. We could reduce the requirements of community supervision—for low-risk and high-risk offenders alike—and spend those taxpayer dollars on more valuable services, such as substance abuse treatment or cognitive behavioral therapy. This would be a good first step toward breaking the vicious incarceration cycle.

Commentary

Study after study shows ex-prisoners would be better off without intense supervision

July 2, 2018