Women’s work boosts middle-class incomes but creates a family time squeeze that needs to be eased

In the early part of the 20th century, women sought and gained many legal rights, including the right to vote as part of the 19th Amendment. Their entry into the workforce, into occupations previously reserved for men, and into the social and political life of the nation should be celebrated. The biggest remaining challenge is how to reconcile women’s new roles in the workforce with their continuing role in the family. Resolving this tension has implications not just for gender equity, but also for middle-class incomes and for the overall well-being of American families.

Middle-class incomes have risen only modestly in recent decades, and most of any gains in their incomes are the result of more women going to work and earning higher wages. But now that most women are employed, that source of income growth is drying up. Although women’s labor force participation has rebounded after falling during the last recession, its long-term growth appears to have stalled. Without new policies and practices that involve greater sharing of the burdens of unpaid work in the home, more support for time-squeezed working families, and higher pay for both men and women, whatever growth we have seen in middle-class incomes may disappear entirely.

Middle-class income growth has been disappointing

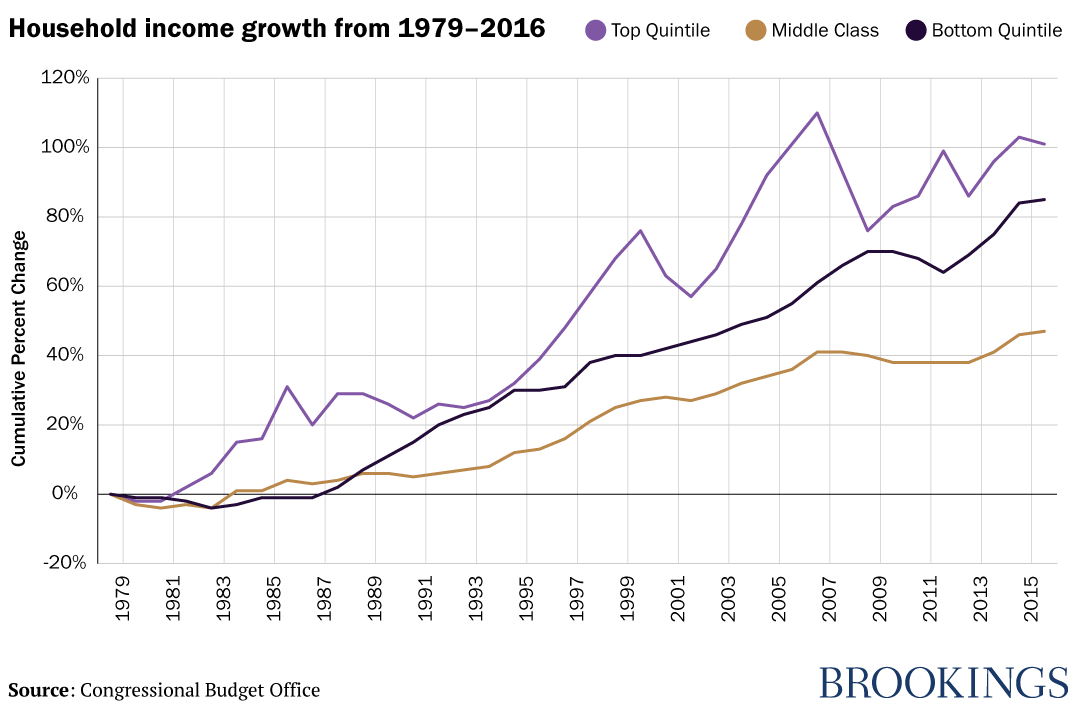

We define the middle class as the middle 60 percent of households, and look at the most recent CBO figures on income after taxes and transfers. Growth in middle-class incomes from 1979 to 2016 was 47 percent, or 1.3 percent per year. That’s a very modest rise considering that we’re looking at a nearly four-decade period. It’s also a slower rate of growth than that experienced by the top 20 percent or the bottom 20 percent over this same period.

The fact that bottom-quintile incomes have grown faster than middle-class incomes may seem surprising. It reflects, in part, the inclusion of the cost of health care in these figures and the expansion of programs such as Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program to many lower-income families. But even when these programs are excluded, middle-class incomes lag behind those at the bottom of the distribution (although by much less).

Without women’s contributions, middle-class incomes would have stagnated

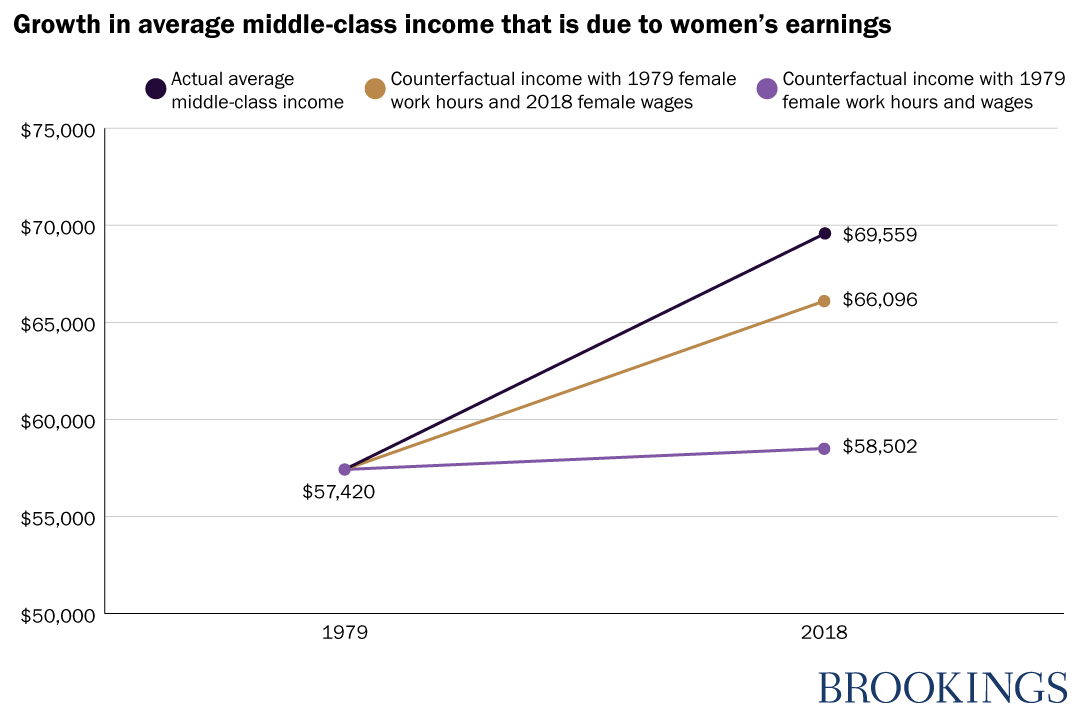

We now come to the interesting part of the story about women and middle-class incomes. Without women’s contributions, these gains would have been small to nonexistent. By our estimates, based on a method initially proposed by Heather Boushey at the Center for Equitable Growth and using pre-tax money income in the Current Population Survey, average middle-class household income grew from $57,420 in 1979 to $69,559 in 2018. If the average contribution of women to household income had not changed, most of these gains would not have been seen. Average income would have increased to just $58,502 in 2018. Women therefore accounted for 91 percent of the total income gain for their families.1

Women’s contributions to family income have risen over this period for two reasons. First, more of them are employed and for longer hours. Second, their average hourly earnings have also risen. Higher wages explain a greater fraction of the increase in family incomes than greater hours worked, but it is clearly the combination of the two (and their interaction) that has enabled middle-class families to get ahead. In addition, as women work more continuously and more of them work full-time, that enables them to compete for higher-paid jobs. If women’s work hours had remained at 1979 levels, but their pay had risen in line with the actual trend, the average middle-class family income would have risen to $66,096 according to our analysis (the middle line on the chart).

Nonetheless, the wage gap between men and women is still sizeable, with women earning about 83 cents for every dollar earned by men. This gap reflects the fact that women are still more likely to be employed in lower-paid jobs, despite being substantially better educated than men. Although some of the existing gap may reflect women’s own choices to work in less demanding jobs with more flexible hours or to take time off to care for their families, some of it reflects a legacy of stereotypes and discrimination that have discouraged or prevented women from being hired or promoted into better-paying jobs.

Without new policies and practices that involve greater sharing of the burdens of unpaid work in the home, more support for time-squeezed working families, and higher pay for both men and women, whatever growth we have seen in middle-class incomes may disappear entirely.

On the employment front, women have made great strides. They now hold a majority of all payroll jobs in the economy, excluding farmworkers and the self-employed. They are also increasingly the chief breadwinners for their families. Over 40 percent of all mothers are either the sole or the primary breadwinners for their families. This includes many who are single parents but also a rising number in two-paycheck families where the wife earns more than her husband. At the same time, their labor force participation rate is still lower than that of men and was until recently in decline.

The bottom line is that without women’s increased employment and earnings, the middle class would not have prospered in recent decades. But this leaves two questions to be addressed. First, how are women managing to “do it all”? Are those families suffering from a time squeeze as women do more paid work? Second, how do we keep middle-class incomes growing now that we are running out of second earners? Can we increase women’s labor force participation rates to equal that of men and close the existing earnings gap? Without further progress, not only will gender equality not be achieved, but middle-class families will lose the main driver that has kept their incomes growing in the past.

Women’s entry into paid work is creating a time squeeze

While women’s entry into the labor market has helped their families avoid a money squeeze, it has exacerbated what we will call “the time squeeze.” This squeeze is most apparent among two-earner families with children and among single parents. But it is occurring against a backdrop of little or no change in normal hours of work in the United States over the past half-century or more. The nation adopted a 40-hour work week in 1940, and that norm has remained in place despite rising affluence which might have been expected to create demands for more time off. Many employers and some states do provide various forms of paid leave, but those policies and practices have so far mainly benefitted higher-paid workers.

In the meantime, the time squeeze is real and made worse by the long hours and limited paid time off provided to most American workers.

The average middle-class married couple with children now works a combined 3,446 hours annually, an increase of more than 600 hours—or 2.5 additional months—since 1975. This average combines dual- and single-earner couples, but the trend is mostly driven by increases in the employment of, and hours worked by, women in dual-earner couples.2

The fraction of couples who are dual earners has risen from about half to 70 percent over the last four decades. The largest increase within this category has been among couples in which both the mother and the father work full-time, reflecting a decline in the fraction with a single male earner but also a shift from part-time to full-time work among mothers. Among dual-earner couples alone, the average couple now works nearly 4,000 hours per year, or 2,000 hours per person. The average single parent in the middle class also works about 2,000 hours per year.

“How are you going to have time to devote to your children and teach them the right values if you’re working so that they can have a roof over their heads and food to eat?”

These dry statistics don’t tell the full story of what life is like for many of these families. Here are a few of the comments made by women in focus groups conducted by Brookings in late 2019:

A woman from Wichita, Kansas said: “I drive myself crazy because I’m almost always multitasking or whatever. I feel like I’m away from my kids a lot more right now than I really want to be. But I’m doing it for a good reason because I’m trying to get ahead or make money, so I can spend more quality time with them more places and do more things. And it’s just a process trying to work through it all.”

Another woman from Wichita added: “I had a second job for a little while, just because I want a little more money, my son’s expensive, and always needs this, this, and that. So, I took a second job, and as soon as I started it, I was like, ‘I can’t do this.’ It was too much. And even though I thought, ’Well, it’s not that much, I can do it,’ as soon as it started invading in on my time, I was done. So, I just had to budget; cut back on some things, refinance some things, because I can’t do it, I can’t do it.”

A woman from Las Vegas asked: “How are you going to have time to devote to your children and teach them the right values if you’re working so that they can have a roof over their heads and food to eat? Because, how are you going to put one over the other? I mean you love your child, you want them to do good in life, you want to be there. But you also want to be able to provide for them. So how do you put focus on which one?”

Women’s responsibilities in the home are constraining their ability to get ahead

The challenge of aligning work with family life has damaged women’s wages and employment opportunities. A significant portion of the gender earnings gap is driven by mothers’ less continuous labor force attachment and lower hourly wages. Women tend to sort into occupations or firms with more family-friendly schedules or policies. They also pay a wage penalty for workforce interruptions and shorter hours. Some of this penalty, and of the overall pay gap between men and women, is the result of outdated perceptions and attitudes that have created stereotypes about what women can and cannot do. Many Americans continue to believe that men should be the primary breadwinners and that women should take care of home and family. For example, among high school seniors, 23 percent believe that this model of men as breadwinners and women as homemakers is the most desirable. These beliefs affect both women’s aspirations and employers’ assumptions and thus women’s opportunities to get ahead. The failure of public policy to keep pace with women’s changing roles has added to the problem. Blau and Kahn (2013) estimate that the United States’ lack of family-friendly policies explains one-third of the decline in women’s labor force participation relative to other OECD countries over the last two decades.

What can be done?

Public policy in the U.S. has failed to keep pace with these profound changes in women’s roles. Despite massive changes in the composition of the work force and in the amount of time being devoted to paid work by women in the child-rearing years, there has been little or no adjustment in the standard work week, in access to paid leave and child care, and in school hours. While men have stepped up what they do in the home, the burden is still highly uneven.

While prime-age Americans work an average of 40 hours per week for 48 weeks of the year, their German counterparts work 35 hours per week for just 44 weeks.

Other advanced countries have done much better. The average American worker spends 200 to 400 more hours at work over the course of the year than workers in most European countries. That’s an extra four to 10 weeks of work. This gap is due to a combination of lower weekly hours and more weeks of leave in other countries. For instance, while prime-age Americans work an average of 40 hours per week for 48 weeks of the year, their German counterparts work 35 hours per week for just 44 weeks.3 It’s time for the United States to adopt similar policies, such as adding a month of nationally-guaranteed paid time off for every American worker to be used for some combination of vacation, illness, and family care. If we want to avoid imposing the costs on employers, the right way to accomplish this is through an expanded social insurance program, financed jointly by payroll taxes imposed on both employers and employees.

Some reallocation of work in the household has occurred, with men now doing a greater share than in the past, but more is needed. Between 1965 and 2011, working-age men roughly doubled their housework time (from 4 to 9 hours per week), while women halved their housework time (from 28 to 15 hours). Time spent in childcare has increased for both mothers and fathers, with mothers still performing about twice as much childcare as fathers. More high-wage job opportunities for women will facilitate greater equality in nonmarket work since women who bring home a bigger paycheck have more bargaining power within the household and are beginning to demand a fairer sharing of work in the home.

We also need some reallocation of work across the life cycle. With rising longevity, it should be possible for people to work longer and retire later. But that should be accompanied by provisions that allow social insurance benefits to be used by parents to take some time off during their children’s early years, as described in more detail in Isabel Sawhill’s The Forgotten Americans. These policies should be gender neutral, providing parental leave to both mothers and fathers on an equal basis but with a “use-it-or-lose-it” provision for fathers as one way to break down current stereotypes and practices.

Finally, the continuing need for out-of-home care must be addressed. Many states have now adopted pre-K programs and Congress recently expanded child care subsidies as well. But a pressing problem is school hours that do not align well with parents’ work schedules. One way to deal with this is for more communities to adopt a voluntary extended school day. Not all of the additional hours need be devoted to classroom pursuits; some might involve extra-curricular activities or extra tutoring or study time for students who need it. To deal with the extra costs, parents could be asked to pay on a sliding-scale based on their income. Local school districts should be allowed to choose what kind of programs might work best in their community but should be required to provide some kind of extended-day option as one way to reduce the time squeeze parents currently face. Instead of every working parent having to make their own complicated afterschool child-care arrangements, schools should be playing the primary role in organizing activities for children still in elementary or middle school during the period from about 3:00 to 5:30 p.m.

Time to tackle time

It has been only a hundred years since women won the most basic of liberties: the right to vote. Since that time, they have made enormous progress in education, employment, and representation in all sectors of American society. One of the most important remaining challenges is the need to reduce the family time squeeze created by the wholesale entry of women into the work force. Policies that address the time squeeze can be a double winner: they should advance gender equity and allow parents to spend more time with their children. If they also serve to encourage women’s participation in the labor market they will also keep middle-class incomes growing. Men have a role to play as well. Unless they contribute more to housework and child care, it will be hard to close the gender gap in employment or in wages.

This is not just a women’s issue; it’s an American issue, and a middle-class issue. Families all across the country are now dependent on a woman’s paycheck. If women are to continue to get ahead and their families are to prosper, we must address the time squeeze.

- These estimates are based on the shift-share methodology developed by Heather Boushey in her book Finding Time and updated in Boushey and Vaghul (2016). We have changed the definition of the middle class used for the analysis and used the PCE deflator instead of the CPI-U-RS to adjust for inflation. The latter change is for consistency with estimates of income growth from CBO reported above. We limit the analysis to households that contain at least one prime-age adult. Income is measured as pre-tax money income. Households are ranked based on size-adjusted household income using the square root scale, but all reported figures are in terms of actual (not size-adjusted) income. These estimates use the Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey (downloaded from IPUMS).

- Based on author’s analysis of Current Population Survey. Annual work hours are calculated as the product of the number of hours usually worked per workweek and the number of weeks in paid employment in the previous year, though this will include weeks of paid time off. Using the American Time Use Survey, in which individuals report time actually worked as opposed to time in paid employment on a daily basis, we estimate that middle-class married couples currently work between 3,241 and 3,560 hours per year, depending on whether breaks at work (such as meals), commuting, and various income-generating activities are counted as work.

- Estimates from Bick, Brüggemann, and Fuchs‐Schündeln (2019).