In the forty years since Iran’s 1979 revolution, no aspect of U.S. policy toward Tehran has produced more heat—and less light—than the question of external efforts to advance political change in Iran. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo stepped squarely into that contested terrain with his speech last year to an audience of Iranian-Americans at the Reagan Library, coming down forcefully in favor of strenuous American and international advocacy but offering little in the way of specific fresh ideas. “While it is ultimately up to the Iranian people to determine the direction of their country,” Pompeo said, “the United States, in the spirit of our own freedoms, will support the long-ignored voice of the Iranian people. Our hope is that ultimately the regime will make meaningful changes in its behavior both inside of Iran and globally.”

Pompeo’s speech met with equal parts praise and scorn. Critics emphasized the checkered history of U.S.-backed efforts toward Iran, from the CIA’s role in the 1953 coup that ousted Iran’s nationalist hero Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadeq, to the Reagan-era Iran-contra scandal, to the Obama administration’s calculated neutrality toward 2009 pro-democracy protests. Many express equal skepticism about any role for the Iranian diaspora, whose passions traditionally have concentrated around the long-exiled son of the late shah or an even more unsuitable alternative, the cult-like Mojahideen-e Khalq, a group whose partisans fought alongside Saddam Hussein.

These concerns are not unfounded, but they may be a bit outdated. A variety of factors, including time and technology, has begun to create new opportunities for expatriate Iranians and others to contribute to charting a better course for the future of Iran. No one demonstrates those possibilities better than Masih Alinejad, a journalist who fled Iran after the 2009 upheaval and later launched an innovative human rights campaign that she chronicles in her new book The Wind in My Hair. With the same audacity that propelled her out of the tiny, impoverished village where she was raised and fueled her crusading work during the heyday of Iran’s reformist press, Alinejad in exile has shattered longstanding assumptions about the salience of external activism.

******

Alinejad’s campaign focuses on one of the central symbols of theocratic rule: obligatory hijab, or modest dress, which enshrined in Iran’s post-revolutionary legal framework on the basis of Quranic injunctions. Her project was born of an expression of joy: a photo that Alinejad posted of herself running through a London street with her hair aloft, which she noted would be a crime in Iran. The photo and message went viral, and that unexpected outpouring of support launched a movement: first, a Facebook page branded as “My Stealthy Freedom” that invited Iranians to post images of themselves without hijab; within a month, the page had nearly 500,000 “likes.” That was followed in 2017 by a hashtag campaign encouraging women to wear white scarves on Wednesdays to protest laws requiring hijab. Alinejad now hosts a weekly show on Voice of America television, and her campaign engages on multiple social media apps, where some of the photos and videos draw millions of views and thousands of comments.

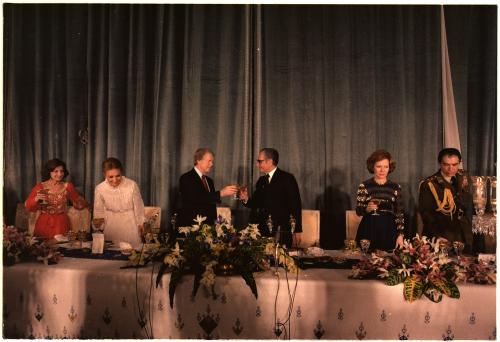

Veiling in Muslim societies has always been heavily contingent on geographic, socioeconomic, and historical context, and in contemporary Iran, the issue has long been politicized. In 1936, the first Pahlavi shah issued a decree that prohibited veiling in a bid to modernize his country and inculcate a sense of national identity; he also mandated European-style hats for men. The edict lapsed a few years later, when the shah was forced into exile and his young son took the helm. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi doubled down on his father’s secular, pro-Western orientation, and in the 1970s, as anti-government activism gained momentum, many women consciously adopted headscarves or all-enveloping chadors as tangible rejections of the monarchy.

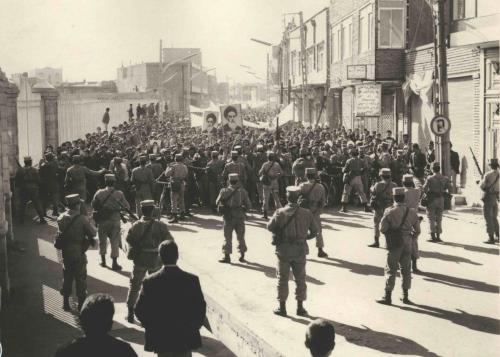

Still, even from the start of the post-revolutionary era, the efforts by the state to impose and enforce hijab provoked intense resistance. In the weeks after the monarchy was toppled, hints of a crackdown on women’s dress prompted some of the first protests of the post-revolutionary era, drawing thousands of women to the streets in March 1979 to warn that the imposition of headscarves by the new leadership threatened their rights. “In the dawn of freedom,” their slogan went, “there is an absence of freedom.”

Despite this and other shows of public opposition, compulsory hijab became one of the essential features of post-revolutionary system, first by force and eventually by law. Today, any violation is punishable by modest fines and a two-month prison sentence. Compulsory hijab was the sartorial manifestation of a broader imposition of legal and cultural misogyny by Iran’s post-revolutionary leaders. They quickly nullified the monarchy’s nascent efforts to advance the status and rights of women and in its place erected a legal framework that enshrines gender discrimination.

Nothing in Iran goes uncontested, and the restrictions on women’s rights have drawn intense pushback over the past 40 years. Advocacy by Iranian human rights activists has re-opened additional professional opportunities for women, mitigated some of the most egregious discrimination in family laws, and inspired creative workarounds to official constraints. And yet, as evidenced by Iran’s near-last ranking on the 2015 World Economic Forum report on the global gender gap, a dense “web of restrictions” on women remains intact. As does the regime’s enforcement of compulsory hijab.

******

Alinejad’s activism was controversial from the start. Iran’s state broadcasters sought to smear her with horrific falsehoods, regime hackers tried to cut off her social media accounts, and she has received death threats from government paramilitary groups. Surprisingly, she has also faced backlash from some expatriate Iranians. Some questioned her focus on hijab, dismissing the fascination with women’s dress as a Western fixation and arguing that Iranian women face more important issues than the piece of cloth on their heads. “Most activists in Iran are more concerned with matters from women’s unemployment to domestic violence,” British author Azadeh Moaveni insisted in 2016. “While mandatory hijab certainly matters, it is for Iranian women to determine what level of priority to accord it.”

Then, in December 2017, on the eve of a spasm of protests over economic issues that briefly convulsed Iran, a 31 year-old mother named Vida Movahed stood atop a utility box on a busy street named for the country’s 1979 revolution, silently waving her white hijab like a flag. She was arrested an hour later, but before she was incarcerated, Iranians captured her quiet rebellion on camera and shared it over social media, where it became one of the iconic images of the brief uprising. A few weeks later, Narges Hosseini climbed upon the same utility box and repeated Movahed’s protests, and over the course of the following months, dozens of Iranian women followed their lead, their images shared under the hashtag Girls of Revolution Street.

In the months that followed, authorities have arrested more than 35 women on charges such as “a sinful act” and “inciting corruption and prostitution;” some have reportedly been tortured and beaten while in custody. Shaparak Shajarizadeh, a 42-year-old who peacefully waved her white hijab from a stick in December, was sentenced to two years in prison in addition to an 18-year suspended prison term. The renowned human rights lawyer who has defended several of the women, Nasrin Sotoudeh, was re-arrested in June after her conviction in absentia on unknown charges. She is serving a five-year sentence and her husband was later detained in a new round of repression that jailed several leading women’s rights activists. Still, Iran’s hijab protests continue: six women were arrested in Khuzestan in July for removing their scarves; in October, a still-unidentified woman climbed atop a turquoise dome in Revolution Square, where a statue of the shah once stood, and waved her headscarf along with a bouquet of balloons. No one seems to know what has become of her, or of the original ‘girl of Revolution Street,’ Vida Movahed. Meanwhile, the commander of Iran’s domestic security forces has announced stepped-up efforts to enforce hijab compliance, threatening to impound the cars of female drivers who fail to cover their hair. The message is clear: Iranian women have no sanctuary from the long arm of the state.

******

Did the Stealthy Freedom campaign helped instigate this wave of activism? Neither Vida Movahed, who waved her white scarf on a Wednesday, nor those who followed in her footsteps have publicly attributed their actions to Alinejad. Several, including Hosseini, have sought to dissociate themselves from any outside involvement. For their part, Iranian authorities clearly saw a connection. On International Women’s Day, the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, gave a blistering speech about hijab, blaming Iran’s “enemies” for trying to “deceive a handful of girls to remove their hijabs on the street.” Since the protests, official efforts to smear Alinejad have intensified, with her family paraded on state television to engage in a Stalinist ritual of denunciation several months ago.

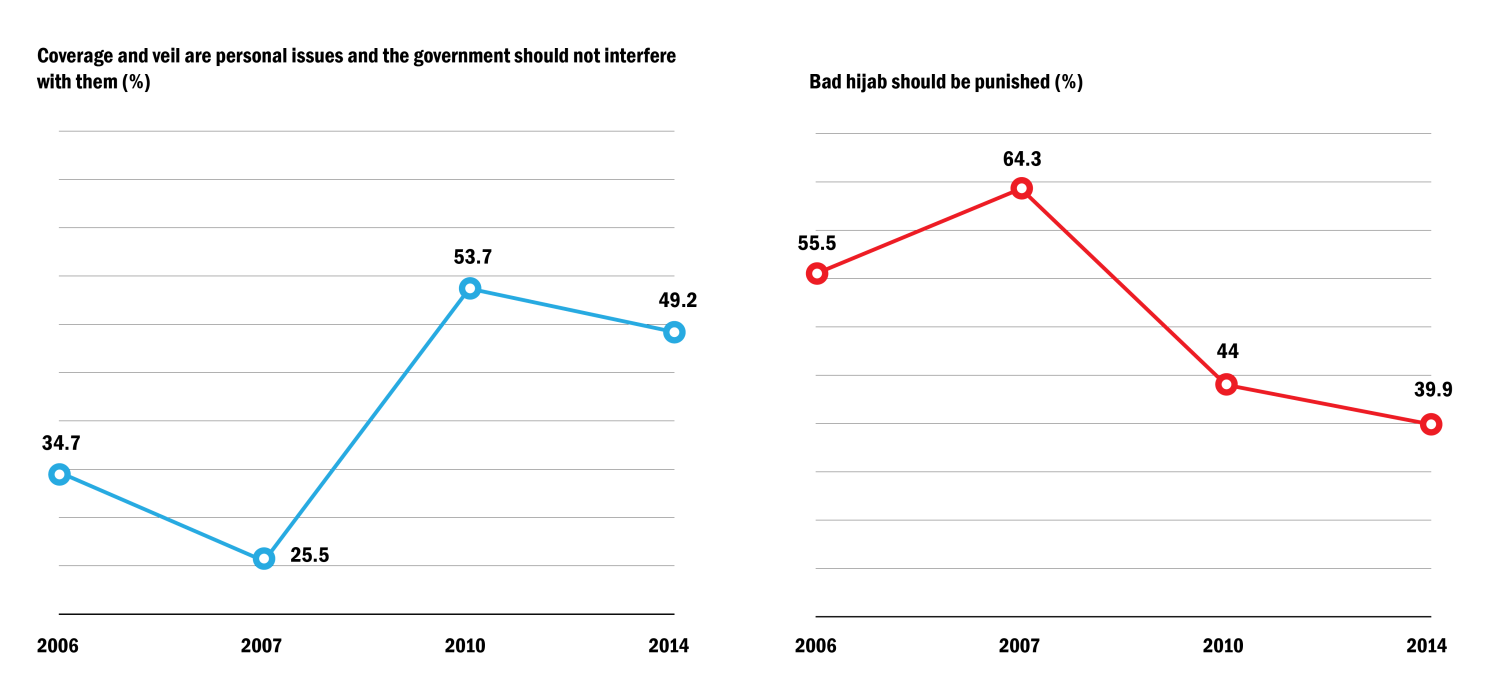

Of course, even as Khamenei insisted that the protests had fizzled, he inveighed against the “journalists, semi-intellectuals, clerics…pursuing the same direction that the enemy is” by expressing doubts about compulsory hijab. Indeed, a number of prominent voices within Iran came to the defense of the Girls of Revolution Street, including a female member of Iran’s parliament who noted that the protestors were “the same girls who for years have been left behind the gates of gender discrimination.” President Hassan Rouhani seemed to hint sympathetically, and in February 2018 his office released a four-year-old public opinion survey showing that at least half the country believes that the government should not require or regulate hijab. A study released last month by the parliament’s research center suggests a steady decline in public support for mandatory hijab.

And in the months that followed, new photos and videos and stories of women removing their hijab or resisting the morality police flooded social media, many via Alinejad, who has become the conduit and the champion of a social movement that is directly challenging the theocratic system.

******

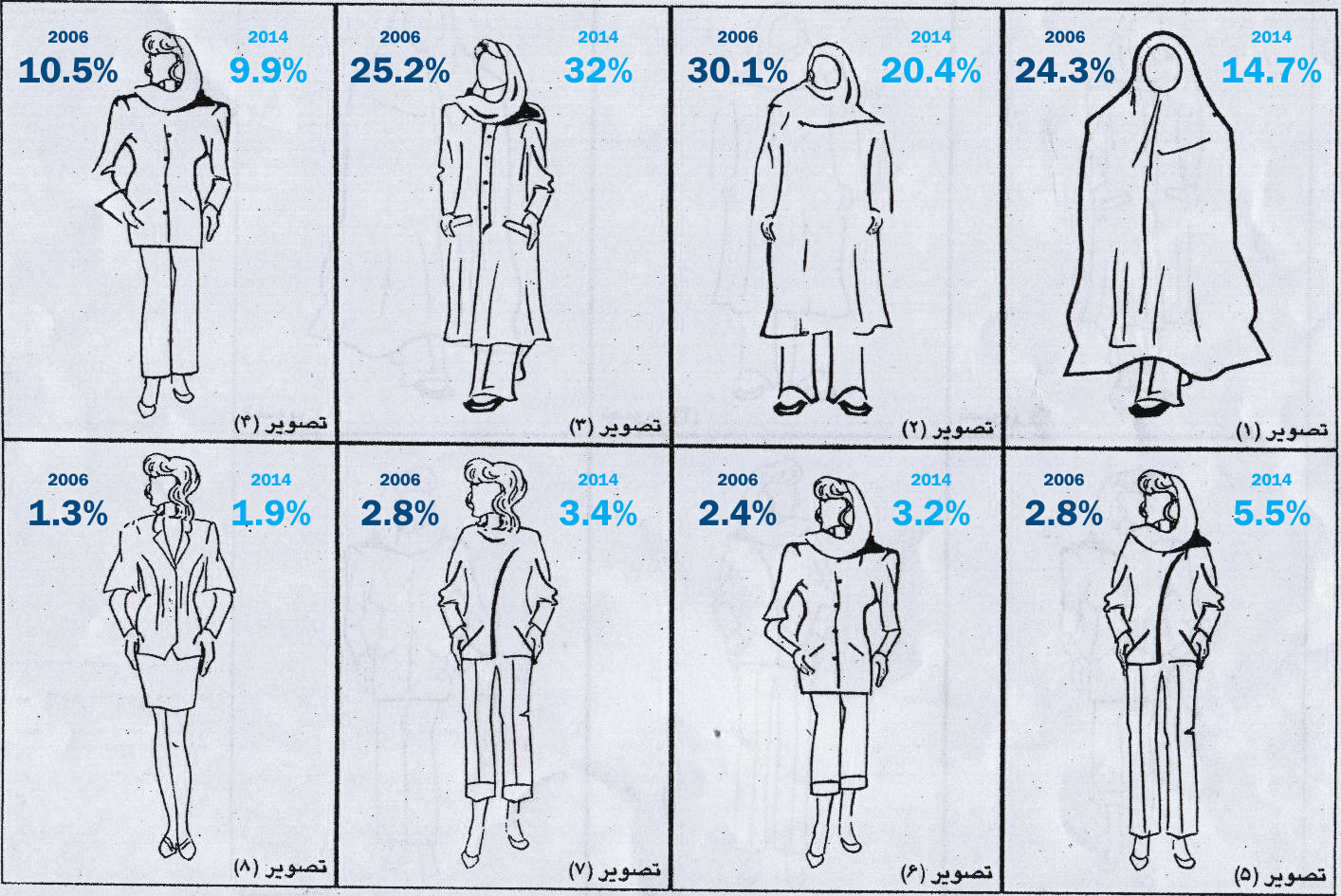

In a country where women require a man’s approval for travel and marriage, where laws surrounding divorce and custody and inheritance favor men, and where female labor force participation is among the lowest in the world despite high educational attainments, it’s understandable that some downplay the significance of hijab “as secondary to other matters such as political or gender equality rights.” Compared to all this, a headscarf may seem trivial. After all, the Islamic Republic’s cultural norms have evolved over time, with steady shrinkage of hems and emboldened colors, and ever-creative Iranians have contrived mechanisms for evading enforcement, including a smartphone app that warned users of nearby morality police.

[I]t’s not about the clothes, it’s about the coercion.

But even with updated styles, the impact of these rules is anything but trivial. By focusing on the legal requirement, rather than re-litigating the theological debate around veiling, Alinejad has helped illuminate how deeply many Iranian women resent compulsory hijab as both the symbol and the instrument of official repression—and the extent to which that repression is meted out disproportionately on Iranian women. In other words, it’s not about the clothes, it’s about the coercion. And that looms large in the day-to-day lives of ordinary women: in the recurrent anxiety about an encounter with the morality police, the discomfort and humiliation of having no agency over something as simple as your wardrobe, the hypocrisy of a system whose public figures extol the chador in public and conveniently discard it while on European vacations. Alinejad’s campaign channeled these frustrations into action, with the invitation to “create your own stealthy freedom so you are not ruined by the weight of coercion and compulsion.”

For something that is only a secondary concern, the Islamic Republic goes to great effort to ensure that its injunctions for modest dress are enforced. Newspapers penciled in a scarf for an obituary feature on Maryam Mirzakhani, a brilliant young mathematician who died in exile; a clerical oversight body retroactively disqualified a successful candidate in the 2016 parliamentary election over leaked photos of foreign travel sans headscarf. Simply organizing a discussion around compulsory hijab can result in detention, and films that mock the morality police have been banned.

As of several years ago, nearly 3 million women received official warnings for loose or “bad hijab” in a single year, with 18,000 cases referred for prosecution. Meanwhile, Iran’s judiciary recently closed the 2014 case of 10 women in Isfahan who were attacked with acid shortly after a law was enacted empowering private citizens to verbally confront those who fail to comply with morality laws. No one was ever charged with those crimes.

For young Iranian women, compulsory hijab is just one manifestation of a ruling system that seems to have criminalized every opportunity for self-expression: dancing, modeling, singing or playing music or shaking hands with men, riding a bicycle, doing Zumba, posting dance videos to Instagram, going to a pool party, celebrating the winter solstice, cheering at a volleyball or soccer match in a public stadium. It is almost as though the Islamic Republic has outlawed happiness. In fact, seven young Iranian men and women were arrested in 2014 for a viral video they recorded of themselves dancing to the song “Happy.”

******

Many Iranian activists and intellectuals sought to effect change by focusing on a broader effort to liberalize Iran’s legal framework, through initiatives like the One Million Signatures for the Repeal of Discriminatory Laws. This agenda meshed neatly with the overall approach of the Iranian reform movement, which emerged as a force to be reckoned with in the late 1990s and sought to use Iran’s routinely disregarded constitutional guarantees as an avenue for strengthening representative rule. That formula promised to temper the system’s excesses from within, and combined with the inexorable force of socio-cultural evolution, some anticipated that this would gradually but inevitably resolve the hijab question.

Unfortunately, that approach has failed—not simply on the question of hijab, but across the board. At every turn, incremental reform has been blunted and subverted by the post-revolutionary structure of power. Reformist victories at the ballot box cannot overcome the levers wielded by unelected authorities who remain committed to preserving the authoritarian control. After decades of public debate, even relatively innocuous improvements, such as permitting women to attend sports matches at public stadiums, remain perennially stalled by clerical opposition, despite evidence of support from across Iran’s factional divide for change. Elections and gradualism change simply can’t overcome the roadblocks of a system where unelected clerics and security officials denounce those who oppose mandatory hijab as “prostitutes.”

Even worse, Iranian leaders became adept at using the debate itself to their advantage, in a seemingly endless game of raising hopes to sustain a modicum of support for the ruling system. The surprise 1997 election of reformist cleric Mohammad Khatami benefitted from rumors that his opponent intended to mandate the most conservative interpretation of hijab, the all-enveloping chador. And in the lead-up to his reelection bid last year, President Rouhani posted a photo of himself on Instagram hiking near Tehran, posed alongside several young women wearing the most modern and minimalist interpretation of the hijab requirement. It was a savvy campaign move; as renowned human rights lawyer Mehrangiz Kar noted at the time, the supreme leader might have done the same if he had to face a popular vote.

Despite his campaign tactics, Rouhani’s five years as president have generated no change in Iran’s policies on women’s dress or more broadly on their legal rights and status. In fact, only months after his risqué photo op and two full decades after resentment of the chador helped sink a prior presidential candidacy, Rouhani required his vice president for legal affairs to supplement her headscarf with a chador, explaining that it remains government protocol. As time passes, gradualism looks more like a hamster wheel, endlessly raising expectations for forward motion before careening right back down to where things began.

******

Alinejad’s campaign, and the hijab protests that have emerged in her wake, reflect a different model of advancing change, one that eschews incrementalism for confrontation and relies on individual acts of civil disobedience rather than collective appeals or coordinated mobilization. This approach has practical value in a country where organized activism exacerbates vulnerability. As one of the Girls of Revolution Street remarked to an interviewer: “This is a kind of movement that does not need to organize and gather people and groups. It is one of the few protests that you can do on your own.”

These solitary acts are amplified by a set of crucial tools—smart phones and social media. Smart phone penetration has increased at rapid rates over the past decade. Whereas in 2009, when massive protests shook the capital and several other cities, approximately 15 percent of Iranians had access to the internet, by March 2018, the country of 80 million people boasted at least 53 million mobile internet devices, according to Iran’s ministry of telecommunications. And this number continues to multiply, by approximately 1 million new devices per month over the course of the past year. 180 million SIM cards are in use today. High-speed connectivity is available in all major cities, and while the government has sought to restrict access to popular messaging apps such as Telegram, along with Twitter, Facebook, YouTube and now likely Instagram—all while the country’s supreme leader and president actively use these platforms— Iranians have become adept at evading official filters.

As a result, the images of the Girls of Revolution Street quickly went viral, inspiring others follow in Vida Movahed’s lead and provoking an intense debate about compulsory hijab that reached all the way up to Iran’s senior leadership. Whatever her role in galvanizing the hijab protestors themselves, Alinejad’s “Stealthy Freedom” advocacy offered proof of concept around the efficacy of hashtag activism in generating new fault lines by interrogating the symbols of state power. A photo circulated widely is not simply a “selfie” when it calls into question the ideological claims of authoritarian control, and videos of Iranian women shouting down the harassment they receive from mullahs and morality police have gone viral.

To question hijab is to question the essence of the Islamic Republic…

And that is precisely what unnerves Alinejad’s critics: her campaign strikes at the heart of the ideology that validates arbitrary and unaccountable power in Iran. To question hijab is to question the essence of the Islamic Republic, and to express those questions in a way that demonstrates impatience with the perennial assurances of “peaceful reform” confounds the deeply-held political narratives of many, both inside and outside Iran.

Whether Alinejad or the Girls of Revolution Street can generate durable policy change is hardly certain. Tehran has massive repressive capacity at its disposal that extends well into the online space. While Alinejad has received thousands of videos and photos of women challenging the hijab mandate, those actively protesting remain a miniscule proportion of Iran’s population. But their actions represent an implicit recognition that a new set of tools is needed to advance change in the Islamic Republic, that instead of working within the beleaguered rules of the game, it is time to contest the levers of power and the symbols that underpin the Islamic Republic’s claims to legitimacy. Instead of gradualism, it is time for at least a hint of confrontation.

And sometimes, even in Iran, it seems possible that more assertive tactics can pay dividends. Iranian women have scored a few modest victories as of late. After years of fierce opposition, in June 2018 women were permitted to enter Tehran’s famed Azadi Stadium for the first time to view a crucial World Cup game from Russia on the Jumbotron. Just hours before the game was to commence, officials tried to shut down the event on the grounds of “infrastructure difficulties.” Thousands of women and men, already gathered outside the stadium to watch the match, refused to leave. After a tense pause, the doors were opened. Without explanation, one small barrier to Iranian women was broken, at least for the day.

******

Alinejad has lived in exile outside Iran for nearly a decade, a factor that has typically undercut the efficacy and relevance of political activism. Post-revolutionary Iran has a disproportionately young population and its politics entail an intense and often personalistic struggle for influence; both of these factors tend to relegate those who operate from a distance to little more than incisive commentary. In Alinejad’s case, distance offered crucial insulation for internet-based advocacy; given the official backlash within Iran, it seems inconceivable that “My Stealthy Freedom” would have survived long if its servers or spokesperson had remained inside the country.

In that sense, she is not alone; a new generation of Iranian activists and dissidents are finding mechanisms for engaging with debates and shaping political outcomes inside the country via journalism sites like Iran Wire, Shirzanan, and Small Media and human rights groups such as the Center for Human Rights in Iran, Justice for Iran, and many others.

The Trump administration has episodically invoked the cause of Iran’s hijab protestors, as part of a broader social media campaign that seeks to highlight human right abuses in Iran. While Alinejad’s message has been amplified by her VOA appearances, the new generation of Iranian expatriate activists don’t require heavy-handed intervention by Washington or other outside governments.

Still, their efforts should prompt a debate about the role for governments and other interlocutors with Iran around the issues they are raising, including compulsory hijab. Without any credible religious rationale, the Islamic Republic has effectively extended the legal mandate for modest dress beyond its own citizenry, to include all women who visit Iran. As Tehran sought to raise its profile for, and revenues from, tourism and entertainment, this has occasionally provoked backlash, with Air France flight attendants forcing the company to change its policy and a number of athletes and chess players refusing to participate in tournaments in Iran rather than submit to Tehran’s wardrobe dictates.

For the most part, however, foreign officials and diplomats have submitted to Tehran’s clothing dictates to avoid alienating or embarrassing their hosts. Even a delegation representing Sweden’s avowedly feminist government deferred to local protocol and donned headscarves in 2017 trade talks. The rare exceptions have generated backlash from Iran’s official media or simply a cheery reprimand from the country’s foreign minister.

The Girls of Revolution Street movement should prompt a belated reconsideration of that approach. After all, a similar transformation occurred in the hijab requirements for foreign officials visiting Saudi Arabia. For a number of years, female U.S. service members stationed in Saudi Arabia were ordered to wear the all-enveloping abaya even as they were helping to defend the country. That policy only changed in 2002, after a female American fighter pilot, Martha McSally—now U.S. Representative (R-AZ) —took the U.S. Department of Defense to court. Since then, senior U.S. and European officials visiting Saudi Arabia have quietly followed her lead; the abaya has been noticeably absent during visits by First Ladies Laura Bush, Michelle Obama, and Melania Trump, as well as Secretaries of State Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and British Prime Minister Theresa May.

Officials from Europe and elsewhere should borrow that script on their visits to Tehran. At a time when Iran’s leadership is especially eager for diplomatic and economic engagement with the West, officials such as European Union foreign policy chief Federica Mogherini could make a simple, powerful statement in support of the fundamental rights that Iranians want and deserve by simply forgoing any deference to forced modesty on their next trip to Tehran. Forty years after Iranian women first went to the streets to denounce mandatory veiling, and a year after a young Iranian woman stood atop a utility box waving her headscarf like a flag, international advocacy for the rights and dignity of all people should not be stealthy.

Commentary

Op-edIran and the headscarf protests

January 24, 2019