Yesterday, in reaction to the recent, dramatic drop in oil prices, Africa Growth Initiative Nonresident Fellow Rabah Arezki and International Monetary Fund Chief Economist Olivier Blanchard sat down to answer seven key questions on this phenomenon. While their analysis mostly looks at the impact of falling oil prices on the global economy, they make the point that these changing oil prices will dramatically hit the sub-Saharan African countries heavily dependent on oil.

The Negative Effect of Falling Oil Prices on African Oil Exporters

The IMF report notes that some African countries are among the most at risk from the fall in oil prices because of their degree of dependence on oil exports. Oil exports account for 40-50 percent of GDP for Gabon, Angola and the Republic of the Congo, and 80 percent for Equatorial Guinea. Similarly, Angola, Republic of Congo and Equatorial Guinea, oil also accounts for 75 percent of government revenues.

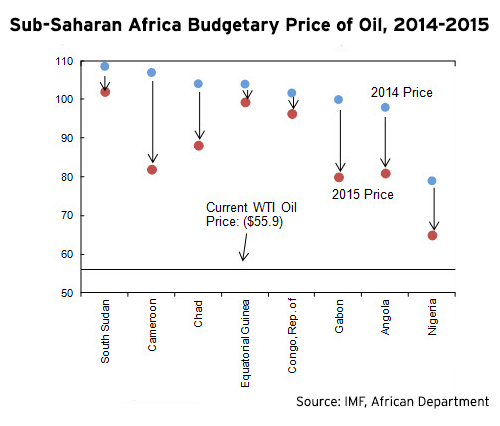

Arezki and Blanchard note that African countries are also vulnerable to falling oil prices in terms of their budgetary oil prices, the oil prices that governments assume in preparing their budget. Chart 10 of a forthcoming report shows the extent to which a number of African governments have reduced their budgetary oil prices to take into account falling market price of oil.

The Exchange Rate Effect of Falling Oil Prices

Arezki and Blanchard also note that lower oil prices typically lead to a depreciation of oil exporters’ currencies and that the drop in oil price has contributed to an abrupt depreciation of currencies in a number of oil exporting countries including Nigeria. The trend is another hit to these oil-exporting countries’ economies.

Other Trends for Sub-Saharan Africa

In addition to the points stressed by Arezki and Blanchard, I would suggest that Africa watchers pay attention to five other important trends specific to the region as oil prices remain low.

Risks to oil-exporting eurobond issuers: Related to the challenges listed above, countries such as Angola, Gabon and Nigeria will find it more difficult to service their debt as their oil revenues fall and the depreciation of their currencies makes U.S. dollar denominated debt more expensive.

Political risk: The economic effects of falling oil prices can increase political risk, especially in conflict countries. According to the Financial Times, South Sudan is receiving the lowest oil price in the world at $20-$25 a barrel because of the combination of falling prices and unfavorable pipeline contracts. As part of the negotiation leading to independence, the country agreed in 2012 to a fixed payment for the use of a pipeline that goes through Sudan, and falling oil prices are eroding their profit margin. The Financial Times notes that Juba bet on a $100-a-barrel oil price and pledged to pay $11 per barrel for the use of the pipeline in addition to a compensation of $15 a barrel to Khartoum for the loss of oil income after independence. Thus, falling oil prices especially do not bode well for South Sudan, which has been war torn for about a year now. Similarly, Nigeria should also watch for increasing investors’ nervousness over Boko Haram. When investors become more risk averse, they typically overlook many of the measures taken by the authorities to manage the impact of falling oil prices.

In addition, some highly oil-dependent countries may not have sufficient fiscal buffers to absorb the falling price of oil. As a result, governments will have to adjust their expenditures and/or devalue their currency, which could lead to higher inflation. Both lower expenditures and higher inflation could be catalysts for social unrest, especially when they affect some segments of society that are quick to voice their discontent such as students and unions.

Benefits to African oil importers: As most sub-Saharan African countries are major oil importers, Fitch Ratings estimates that the plunge in oil prices this year could boost the region’s growth to 5 percent in 2015 from 4.5 percent this year. Countries such as Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Seychelles and Ethiopia spend more than 20 percent of their import bill to buy oil. Not surprisingly, portfolio investors targeting Africa are now focusing more on oil-importing countries and looking away from oil-exporting countries. Bloomberg reports that stocks have surged 22 percent in Tanzania, 18 percent in Uganda and 9.4 percent in Kenya (NSEASI) since oil began falling from a peak of $115.71 a barrel on June 19, while the benchmark Nigerian stock index fell by 24 percent.

Volatility in local currency markets in oil-exporting countries:

Central banks in oil exporting countries face a difficult task as local currencies are depreciating.

In Nigeria, recent

measures

taken by the central bank are trying to fight speculation against the falling naira, which fell by 10 percent since mid-June this year—the second-largest fall among the 24 African currencies tracked by Bloomberg. However, these measures make it increasingly difficult for foreign investors to obtain foreign currency in exchange for nairas when they want to exit their positions, and may discourage new investment.

Risks to future African oil exporters:

Although oil-importing countries such as Kenya and Uganda are gaining from the current fall in oil prices, they are set to become oil-exporting countries, perhaps as early as 2017. As such, falling oil prices may reduce the expected profitability of their investments in the oil sector. However, some

observers

note that exploration projects in these countries have been onshore and thus will be cheaper to exploit than offshore projects.

In their commentary, Arezki and Blanchard include a number of policy recommendations that should be of interest to any sub-Saharan Africa observer. For instance and not surprisingly, they recommend that countries use the fall in oil prices to decrease energy subsidies and use the savings toward more targeted transfers, and for some to increase energy taxes and lower other taxes. I would only add that in an election year, as is the case in Nigeria, the incumbent government will certainly avoid fighting such a battle before the elections. But overall, I would strongly recommend the piece by Arezki and Blanchard for any Africa watchers.

Commentary

Falling Oil Prices and the Consequences for Sub-Saharan Africa

December 23, 2014