With plenty of politically-sparked disasters and crises around the world, readers of the Brookings website might be forgiven for not wanting to hear about additional, imagined catastrophes.

But as the United States thinks ahead to the capacity of its government for handling various hypothetical problems, ranging from the size of its Army and National Guard to its AID and other relief capabilities to its coordination with the NGO and private sector worlds, it is important to have a sense of the possible.

More exactly, it is important to think about what is plausible. Of course, many things are possible, including asteroid strikes, a reversal of the Earth’s magnetic field, and tornadoes that might take down the heart of the federal government in D.C. But the odds of such disasters are thankfully extremely low—perhaps low enough that we need not actively plan for them in advance.

That said, we need to broaden our imaginations beyond the disasters that have afflicted the world over the last couple of decades. As terrible as they have been, it is possible to imagine much worse, either from a single event or a one-two punch from Mother Nature.

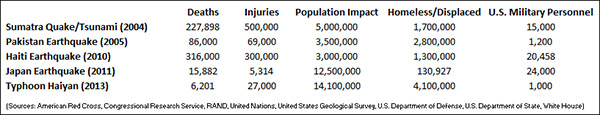

Comparing large international natural disasters in recent history.

To be sure, there have been ample natural catastrophes in the world in recent times, and with a wide variety of characteristics as well. A partial list would include, just in the last 10 years, the 2004 tsunami near Indonesia, the 2005 Pakistani earthquake in remote Kashmir, Hurricane Katrina near New Orleans that same year, the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the 2011 earthquake and tsunami leading to the nuclear disaster in Japan, the 2013 typhoon in the Philippines. There have been earthquakes in China and Iran as well, Superstorm Sandy along the U.S. eastern seaboard, and a host of contagious disease outbreaks with the current Ebola virus outbreak the latest scare.

But as bad as these disasters all have been, as absolutely terrible for their victims and the victims’ families, one is also struck in surveying the data—as we have for an ongoing Brookings research project—that things could have been worse. Most of the biggest disasters struck in places that, while not underpopulated or remote, were also not in the most densely populated parts of the planet. Moreover, with the exception of the Japanese earthquake/tsunami/nuclear accident, most of these catastrophes were one-offs.

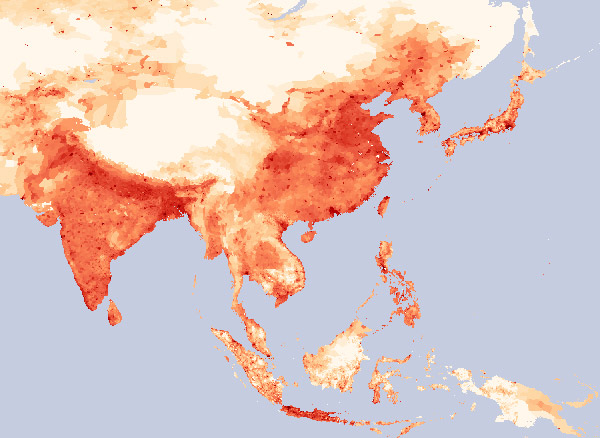

Population density of Asia and the Asia-Pacific. Darker colors indicate more people. (NASA)

Each of the biggest events listed above affected, most acutely, areas with combined populations of 1 million to 5 million. They did not hit the world’s largest megalopolises. And while they did take aim at poor countries with limited capacity to respond in several cases, they did not hit nations with ongoing civil crises or wars whose basic political stability could have been further compromised by devastation from Mother Nature.

Let us hope it remains that way. But as global populations grow, especially along the Asian littoral, and as certain storms or large-scale weather patterns are perhaps intensified or at least shifted by climate change, we need to be ready for worse.

Superimposing the bands of devastation from some of the above on more populated areas helps one see the realm of the plausible. What if the Fukushima nuclear accident had affected reactors near Tokyo, with its population of some 30 million? What if a future Typhoon Haiyan targets Shanghai? What if a massive earthquake hit Karachi, Pakistan or sent a tsunami into the heavily populated areas of coastal East Asia?

Typically, international response contingents for recent tragedies have numbered in the low tens of thousands of personnel at peak levels of activity. But it is easy to imagine tragedies that could drive these figures roughly a factor of ten higher. We need to think about how to be ready.

Commentary

U.S. Capability to Respond to the Next Great Disaster

August 12, 2014